A few days ago, we learned about the –premature– death of Luther Price. It is not in our custom to publish obituaries, but the time Luther Price was part of (S8) was so meaningful that we felt compelled to find a way to pay tribute to him and say goodbye. Price’s time with us was short, but the mark he left is deep, as Ana Domínguez pointed out in our chat.

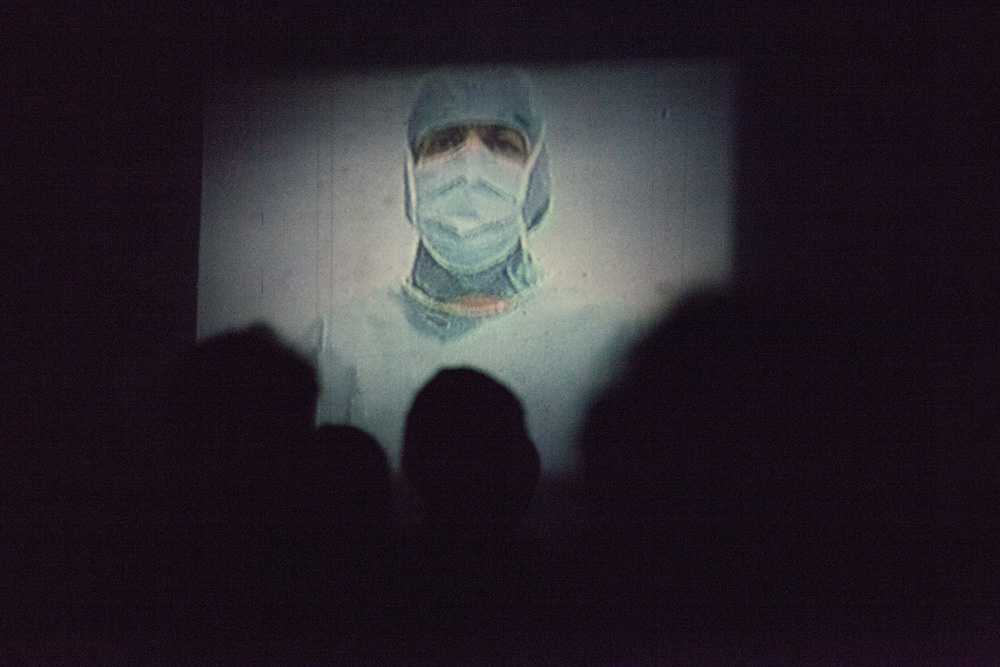

He visited us in 2017. That year’s edition, Objects and Apparitions, was dedicated to found footage cinema. Thanks to Ed Halter’s precious help, we built a program focused on Price’s found footage works, which was complemented by an exhibition of his slides: images by other people that Price had (literally) baked or buried. It was a sight of unsettling beauty, of balsamic horror. There are, indeed, very few people in the world that relate to cinema in the visceral way Luther Price did: each one of his films feels as if a strip of his own skin had been ripped out of his body and then put on show for us to see. Sure, Price physically and repeatedly tortured his found footage (he pierced, painted, buried, soaked, ripped it…), but there was more than that to it: the very content of each image revealed the honest and profound connection that Price developed with it. His is a cinema of wounds –of trauma, pain, sex, and violence… but also of healing, therapy, and redemption. Price’s own words about his film Fancy (2006), here remembered by Halter, are very revealing: “An excruciating montage of medical footage showing bodies being clamped, probed, sliced and sewn. Price sees Fancy as a film about healing and repair: ols bodies being re-edited and remade, like just the tissues of the film.”

Price, who lived in Revere, Massachusetts, started working with filmed material in the 80s. He used a number of pseudonyms, including Brigk Aethy, Fag, and Tom Rhoads, until he adopted –almost permanently– Luther Price, a combination of the names Martin Luther King and Vincent Price (Luther’s birth name was as original and exotic as his pseudonyms). He began working with super 8 after having being shot in a violent incident during a trip to Nicaragua, an experience that left him with lifelong sequels. Part of his creations, like Green, were made with material he himself filmed (the results of a performative inclination that he cultivated in different ways), while others were composed using found footage, as is the case with his masterpiece Sodom, the first film he signed with the name Luther Price. Sodom is a collection of pornographic images of men that fellate themselves and have sex with each other; a succession of wild images mutilated and recomposed in different ways and edited so as to create a meditative rhythm (that remains present even in the most frenzied bits), combined with a soundtrack of Gregorian chant.

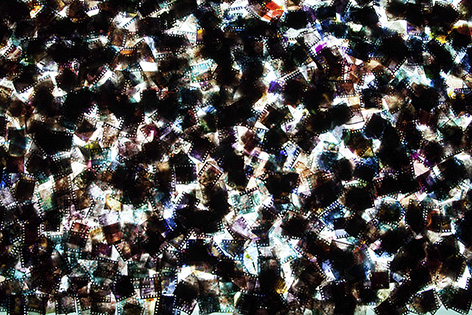

In the 90s, Price started working in 16mm, almost exclusively with found footage. He made several series of films, such as his collections Inkblots (for which he degraded the film emulsion to later paint over it), Ribbons (16mm films onto which he pasted strips of super 8 footage), Garden Films (a series of films that he buried and then exhumed), and Biscuits (creations based on repetition for which he used a set of identical prints from a nursing home for black people). All these films include images of family life, hospitals, and sex – three topics that resonated deeply with him. But cinema wasn’t the only medium Price explored. He created a number of sculptures and manipulated series of film slides by different means: using them to make collages, burning them, baking them, exposing them to organic substances… The content of these representations was eclectic, too, and included domestic scenes, religious icons taken from diverse films, movie trailers, medical equipment, and exposed flesh –human flesh bound to all kinds of impulses, decay, and rotting.

The tragic, violent, eschatological, and mysterious aura of Price and his work was, as we could see by ourselves, the public side of a harrowing sensitivity. In each one of his screenings and Q&A sessions we discovered that films were, for Price, an expression of brutal honesty, an exposure to the world filled with meaning and emotion. It felt like he was risking his life with every screening in the same way he risked the physical integrity of his films, most of which were a corrugated jumble of material. This actually made them unscreenable in most places –a delicate issue. His carousels of slides –loaded with many wonders– came to us with a bunch of baked-and-buried stray frames that we could touch and even keep as a souvenir.

Before leaving, he distributed, among all the members of our team, his own clothes and accessories –the garments of the studied outfits he had packed for every occasion. A 5-minute conversation with him was enough to leave a deep impression on you. The expression “to tear oneself open”, today a tedious cliché, could easily have been coined to describe Price’s way of being in the world. All this was sprinkled with irresistible charm and intelligence, and a singular sense of humor. We say goodbye to him as we would to a good old friend, with tears coming to our eyes. The night before he left Galicia back in 2017, we saw him disappear into the dark to bury –or maybe leave among the rocks at sea– one of his rolls of found footage that still lies hidden somewhere in A Coruña.

We’ve been incredibly lucky to have shared our time with Luther Price, whose mortal flesh has experienced what many of his films did, but whose beautiful, tortured personality will always stay with us.