THE MECHANICS OF LIGHT

Wednesday June 2 | 6:30 pm | Filmoteca de Galicia | Get your free ticket here

Cinema came into existence thanks to the invention of a series of mechanical devices that are able to capture light and make an impression onto a film strip. Light takes a round trip: to project the registered images, it is radiated back by those very devices –a troop of allies that work always in the shadows (literally and metaphorically), and whose mechanisms and procedures are rarely seen onscreen. Invisible are the mechanisms that incite us to see… with purposes that may vary widely. In Ken Jacob’s words,

After the very earliest public screenings projectionists had been tamed and toying with direction and tempo gave way to uninterrupted absorption in subject matter. Film was relegated to a straight-ahead fixed-speed carrier (“Tote that star! Deliver that story!”), mechanism was expected to remain humbly invisible and not interrupt the trance. Invisibility would be furthered by developments in synch-sound. wide-screen color and verisimilitudinous 3D… Somewhere there is film, sitting alongside the sunset, both wondering why hardly anyone comes around anymore to see them do their stuff.

The Mechanics of Light is a program intended to take us on a trip back to a time when the very existence and mechanics of such devices was what filled us with wonder. Its aim is to bring to the audience a collection of films that delve into the nature of film, exploring cinema itself by bringing into play (and sometimes into the frame) the main tools that make it possible. Let’s go watch machines do their thing. Let’s go to the cinema… to watch cinema be.

This program will be devoted to exploring the camera as a device through a selection of films where cameras and their mechanisms are the protagonists. A movie camera is basically a dark box equipped with a lens that allows light in it in order to expose a film strip thanks to a reeling system. A number of elements are then added to this basic setup: a viewfinder, a diaphragm, a shutter. All of them are at the core of our program: the Austrian filmmaker Dietmar Brehm portrays them frontally, in a mirror. He shows the camera, the operator, all the actions that are performed with it and their results in real time –a film whose simplicity contrasts with the power of its images.

Christian Lebrat brings to us another self-portrait of the filmmaker with his camera. In his film, the image unfolds into many copies of itself through the use of multiple mirrors. Lebrat uses a homemade contraption to alter the images registered by the original device.

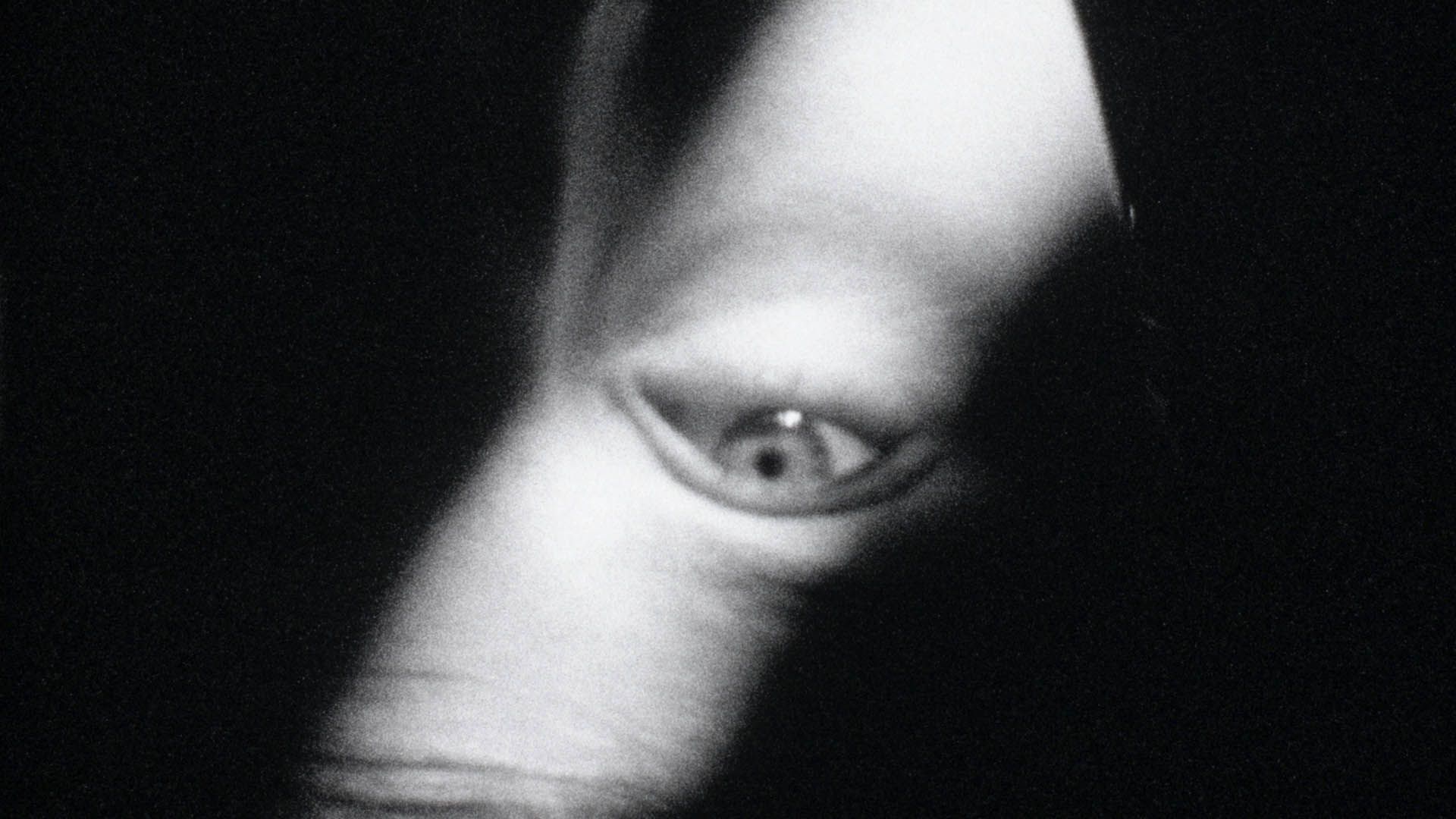

Okuyama’s film was made with a camera that the director –like many of the authors featured in this selection– designed and built ad hoc for this project; a device that allowed him to create unique superimpositions.

Using masking techniques and painted glass, Yonay Boix suggests that the world is seen through a hole in a camera obscura, in a super 8 film that was edited, precisely, in-camera. Pablo Marín, in turn, uses a “prepared camera” (in the sense of John Cage’s “prepared piano”) –a super 8 camera equipped with a modified viewfinder that allows him to produce several layers of film and catch them with a “light trap” (trampa de luz).

Chris Welsby uses his windmill as a secondary, external shutter whose rotation creates a mirror effect, in a film where the camera expands beyond its physical limits.

These films will be followed by three pieces that explore the pinhole camera as the level zero of photographic cameras –a cardboard box without a lens but with a tiny aperture that allows light to enter the box and create an impression onto a piece of photosensitive paper. Film Stenopeico, by Paolo Gioli, was created with a peculiar homemade movie camera that integrates a reeling system designed by the author. The simultaneous, vertical images produced by this device in a single shot extend through when the film is mounted onto a projector.

Using a simple mechanism, Australian filmmaker Dianna Barrie turns a super 8 cartridge into a pinhole camera and experiments with it by means of an even more ancient tool. Philipp Fleischmann makes use of a device similar to that used by Gioli. Fleischmann’s contraption, however, was conceived and built ad hoc to adapt to the filmed architectural space.

The final piece that will close this first session is Projector Obscura, a film by Peter Miller where he uses a projector as a movie camera (an idea that traces back to the first film cameras built by the Lumière brothers, which worked as film projectors too).

KAMERA | Dietmar Brehm, Austria, 1997, 16mm, 9 min.

In the spring of 1997 I placed the camera in front of a mirror and filmed the camera and myself at the same time as manipulating the camera in ways not recommended in the instructions for use. When the film came back from being developed, I was forced to think “Whew”. The camera looked much better than I did and I wanted to destroy the film immediately. (Dietmar Brehm)

AUTOPORTRAIT AU DISPOSITIF | Christian Lebrat, France, 1981, 16mm, 9 min.

The element on which it is based is a roll of perforated paper which functions as a manual shutter for the making of Holon. This film could be seen as within the tradition of classical painting using mirror-like devices (the Arnolfini Portrait by Van Eyck or Las Meninas by Velázquez are the best known)and numerous self-portraits throughout the history of art (the 1650 Self Portrait of Nicolas Poussin at the Louvre comes particularly to mind). The issues that they deal with are similar: representation of the artist with his tools, the illusory aspect of representation, a declaration of the device employed. (Excerpt from “Christian Lebrat, The Liberation of Color” by Olivier Michelon)

LA FACE ET LE DOS EN MÊME TEMPS | Jun’ichi Okuyama, Japan, 1990, 16mm, 6 min.

To create this film, Okuyama equipped a camera with two lenses –the first filmed the author from behind, while the second filmed him frontally. This mechanism allowed him to obtain two overlapping images of himself.

WINDMILL II | Chris Welsby, United Kingdom, 1978, 16mm, 8 min.

The camera films a park landscape through the blades of a small, hand-built windmill. Each of the eight blades was covered in Melanex (mirrored fabric). The film was shot on a windy day in the park, with three 100-foot takes being shot on the same day. The camera angle remained the same throughout. Variations in wind speed and direction cause a constantly shifting relationship between the landscape in front of the camera, as seen between the blades of the windmill, and the reflection of the camera with the landscape behind it. (Chris Welsby)

#005 | Yonay Boix, Spain, 2021, super 8 to HD video, 3 min.

The fifth cartridge exposed by Yonay Boix’s super 8 camera offers a continuation of the author’s filmed journals that he carefully composes frame by frame, exploring the potential of celluloid and in-camera editing. This time, the leitmotiv is either a spot of light or a dark spot that he generates using a pierced piece of paper and a glass filter onto which he has previously painted a black dot, respectively. These procedures trace back to the mechanisms of early cameras, reminding us that what we see is not the world but the glimpse of it that a contraption was able to catch.

TRAMPA DE LUZ | Pablo Marín, Argentina, 2021, super 8 to HD video, 9 min.

“Fire insubstantial, sacred and enclosed, earthly fragment to the light exposed.” Paul Valéry, The Graveyard by the Sea (1920)

FILM STENOPEICO | Paolo Gioli, Italia, 1974-1989, 16mm, 13 min.

This film, as the Vertovian title indicates, was made without a movie camera, more precisely with a device custom made to restore to images freedom from optics and mechanics. This strange movie camera is a simple hollow metal tube, one centimeter thick, two centimeters wide, and a little more than a meter long. At the ends, two reels hold 16mm film. Film is pulled through manually causing alternations of time and space. The images enter simultaneously through 150 holes distributed along one side in proximity to each frame, that come to make up 150 tiny pinhole camera obscuras. One of the most obvious results will be to find oneself confronted precisely with a movement of the camera that never happened; somewhat magical pneumatic flutterings running longitudinally and transversally along a face and body reconstructed through 150 image points. (Paolo Gioli)

SELF PORTRAIT WITH BAG | Dianna Barrie, Australia, 2020, super 8 to 16mm, 6 min.

A camera-less portrait of the artist. Super 8 cartridges placed inside a black cotton bag, the film advanced via a hand crank. The tiny gaps in the fabric weave make for dozens (hundreds? thousands?) of tiny pinholes.

AUSTRIAN PAVILION | Philipp Fleischmann, Austria, 2020, 35mm, 4 min.

One of the principal global art events, the Venice Biennale, has never screened leading experimental films from Austria. The filmmaker extracts a 35mm ‘light print’ from the art space using specially developed cameras creating an exhibition solely for the cinema.

PROJECTOR OBSCURA | Peter Miller, USA, 2005, 35mm, 10 min.

Projector Obscura is a series of films that are exposed using projectors rather than cameras. The similarity between motion picture cameras and projectors is such that if a projection booth is adequately darkened and unexposed film is run through a projector, light illuminating the theater will enter the projector lens and expose the film. The theaters recorded in this project are the Biograph, the Gene Siskel Film Center, Anthology Film Archives, Gateway, MFA-Boston, Coolidge Corner and Harvard Film Archive.