Thanks to La Vida Útil, one of the publishers invited to our meeting of experimental film publishers on Sunday 4th June (together with Lumiére, Stereo Editions, Eyewash Books, Black Box and Hatje Cantz), we are publishing a fragment of Una luz revelada. El cine experimental argentino (A light revealed. Experimental Argentine film), by Pablo Marín; a small sample of his work.

There is something heroic about Super 8. It’s a format that wants to be huge.

Steve Polta

As opposed to the historical point of view that considered Super 8 to be a kind of aesthetic enclosed in itself, corseted within its physical dimensions, there is a constellation of small-but-huge films that stretches out across decades and territories with the power of an epic tradition, as rightly pointed out by Polta, a filmmaker and curator from the United States. Backed by a set of films that are aware of the liberating power of their restrictions more than minimalist cinema, this parallel, non-negative history of the format finds some of its deepest roots in latitudes where economic conditions hindered the development of accessible professional film practices. It is no coincidence that the aforementioned texts come from North American authors, from a land in which experimental cinema took its first steps and reached maturity running parallel to the industry, while somehow taking advantage of many of its resources. Nor is it by chance that much of Super 8 film that is different from that consideration—though not necessarily contrary to it—comes from countries like Brazil, Mexico and, perhaps more radically, Argentina. It is no coincidence because, at the risk of making a long and complex story short, in such countries (and in Argentina specifically) the absence of a professionalised and accessible independent work in 35 mm and 16 mm (the lack of filmmakers’ cooperatives is a fact not to be overlooked) culminated in the acceptance of Super 8 as the ideal medium for making films based on a free and artistic stance1. It is as if the lack of choice brought about a following that soon turned into devotion. Comolli and Sorrel understood this paradoxical circumstance by noting that “film history teaches us that filmmakers who want to film off the beaten track only seldom resort to the latest advances in technology. They prefer less complex cameras, without a doubt, but which give them more freedom”2. In this way, driven by the economic situation towards Super 8, it was experimental Argentinian filmmakers who ultimately only used an approach that paid little attention to generalised opinions to drag the format out of that preset aesthetic context towards a higher level of rigorous ambition answering to the same unique interest: the possibility of getting the highest level of quality out of the least grandiose of means3.

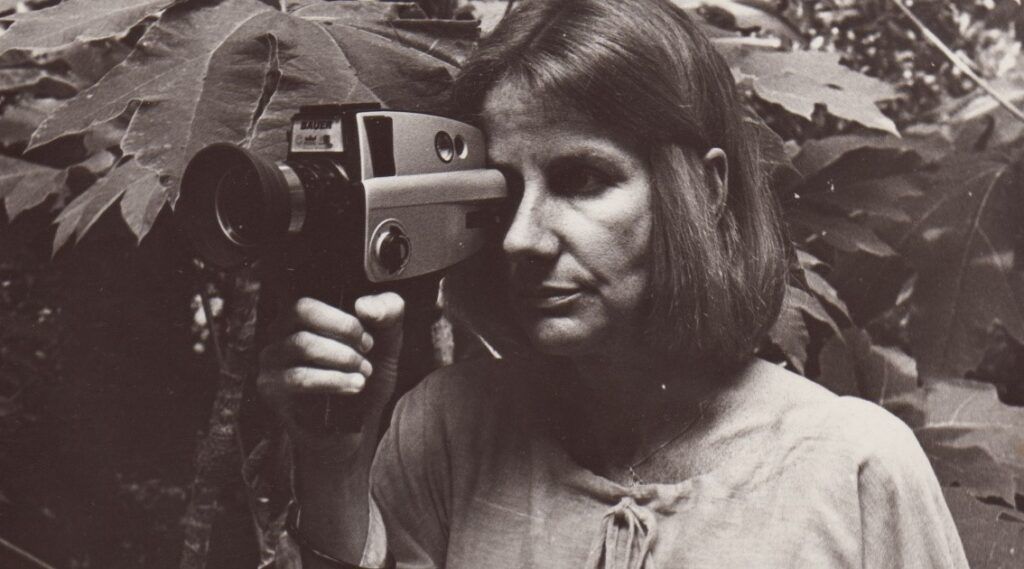

As in the rest of the world, Super 8 arrived in Argentina in the mid-sixties, but it was not until the early seventies that it reached the hands of the general public en masse. Outside of the strictly recreational home movie sphere, the format made its way quickly—and one might say explosively—towards a more ambitious use split between a “professional” activity that sought to emulate the small-scale film industry, and a creative search to introduce cinema to the artistic revolution that had begun a decade before within the cultural panorama of Buenos Aires. This debate between tradition and modernity materialised in the sphere of reality in the distinction between the work carried out by UNCIPAR, created in 1972 with the aim of “provid[ing] its associates with an open screen for their films, technical orientation courses, discounts and special services in shops, etc.”4, and the echoes of the Audiovisual Experimentation Centre at the Di Tella Institute. The latter was interested in promoting “experimentation and research into new media of audiovisual expression”, which would later resonate more intensely in specific areas such as the Filmoteca studio—created in 1969 by Silvestre Byrón—and especially the Goethe Institute in Buenos Aires under the initiative of Marie Louise Alemann and Narcisa Hirsch.

- Beyond economic rationality, it could be argued that there was also a reason for rejecting what the professional and semi-professional formats represented, since they were linked to commercial, industrial practice. The fact that Claudio Caldini abandoned an official filmmaking course at the National Institute of Cinematography after a year of studying says a lot about this sort of disenchantment and alternative quest.

- Jean-Louis Comolli and Vincent Sorrel, Cine, modo de empleo. De lo fotoquímico a lo digital (Cinema, ways of use. From the photochemical to the digital), Manantial, Buenos Aires, 2016 p. 51.

- Of course, this does not mean that geographical or economic factors have been decisive in the difference between the approaches to Super 8 (that would mean perpetuating a discourse fascinated with the idea of peripheral resistance); but that, at the very least, they seem to have acted as a spark, as the initial context for a primarily aesthetic process.

- Guía Heraldo ‘78, op. cit., p. 371. The Paso Reducido Filmmakers Union was undoubtedly the standard bearer of amateurism with a professional vocation during the heyday of Super 8; the flagship of a fleet of film groups and societies that were active throughout Argentina and which included, among others, the Foto Cine Club Klik in Mar del Plata, the Ateneo Foto Cine in Rosario and the Peña Foto Cine 8 mm in La Plata.