RHAYNE VERMETTE

PROGRAMME 1

Sala (S8) Palexco | Wednesday June 5th | 5:00 pm | Free entry to all venues until full capacity. It will not be possible to enter the venues after the screening has started

U.F.O.

Rhayne Vermette | 2016 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 2 min

In this very short animation, an apparition reveals itself through celluloid and transmits vestiges of a forgotten provenance. Have the onlookers interpreted its signs correctly or was the message misunderstood? Inspired by found sound of two people’s discovery of a mysterious event in the sky. (National Film Board of Canada)

TRICKS ARE FOR KIDDO

Rhayne Vermette | 2012 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 2 min

In 2010, Winnipeg director, Guy Maddin exclaims “it’s impossible to collage a film!” (Rhayne Vermette)

EXTRAITS D’UNE FAMILLE

Rhayne Vermette | 2015 | Canada | Super 8 to HD | 7 min

This film is my failed attempt at creating a thematic palindrome of audio/visual samples. When working between two poles of remembering – one easily gets confused. Please enjoy this film before my mother asks me to delete it. (Rhayne Vermette)

LES CHÂSSIS DE LOURDES

Rhayne Vermette | 2016 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 18 min

“…while many architects through their time have sought a ‘true house’ or a ‘true architecture’, their truth was something of the past and not so true in the present […] here architecture is a child of the sea, arose from its substance (architecture is always conceived from the interior)…” (Gio Ponti)

At the age of 32, I finally ran away from home. Dramatically, I left with only my cat and copies of all the still and motion images taken by my father (these dating until the mid 1990s when he then passed his camera down to me). And while I unpacked the baggage of this surreal house coincidentally, back home, renovations were in order… Here, an architectural threnody is composed through a falsified genealogy of image making and various “true stories” of Lourdes. What time is it? No time to look back. (Rhayne Vermette)

J. WERIER

Rhayne Vermette | 2012 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 4 min

An architectural portrait emerges as a transmogrification through various broken projectors. These particular projectors are currently being sold at J. Werier, a Winnipeg warehouse emporium and artifact. (Rhayne Vermette)

FULL OF FIRE

Rhayne Vermette | 2013 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 2 min

There are few alternatives for exiles. The homecoming may be postponed to an indeterminate future; one could settle for a replacement; and lastly, there is always madness. (Rhayne Vermette)

BLACK RECTANGLE

Rhayne Vermette | 2014 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 2 min

“Time has not been kind to Kasimir Malevich’s painting, Black Square. In 1915 when the work was first displayed the surface of the square was pristine and pure; now the black paint has cracked revealing the white ground like mortar in crazy paving.” (Philip Shaw)

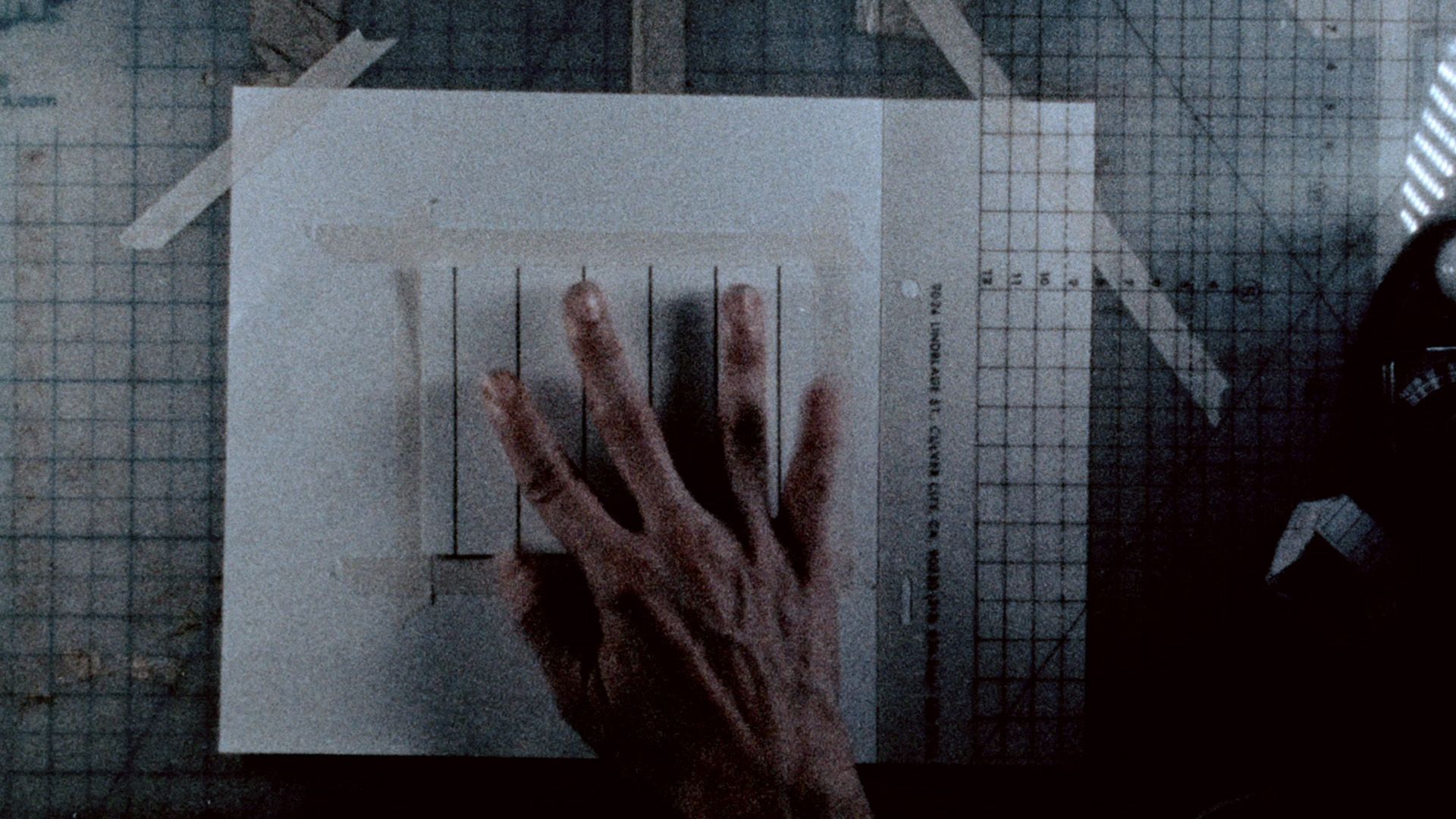

This film documents a tedious process of dismantling and reassembling 16 mm found footage. The film collage imitates functions of a curtain, while the recorded optical track describes the film’s subsequent destruction during its first projection. (Rhayne Vermette)

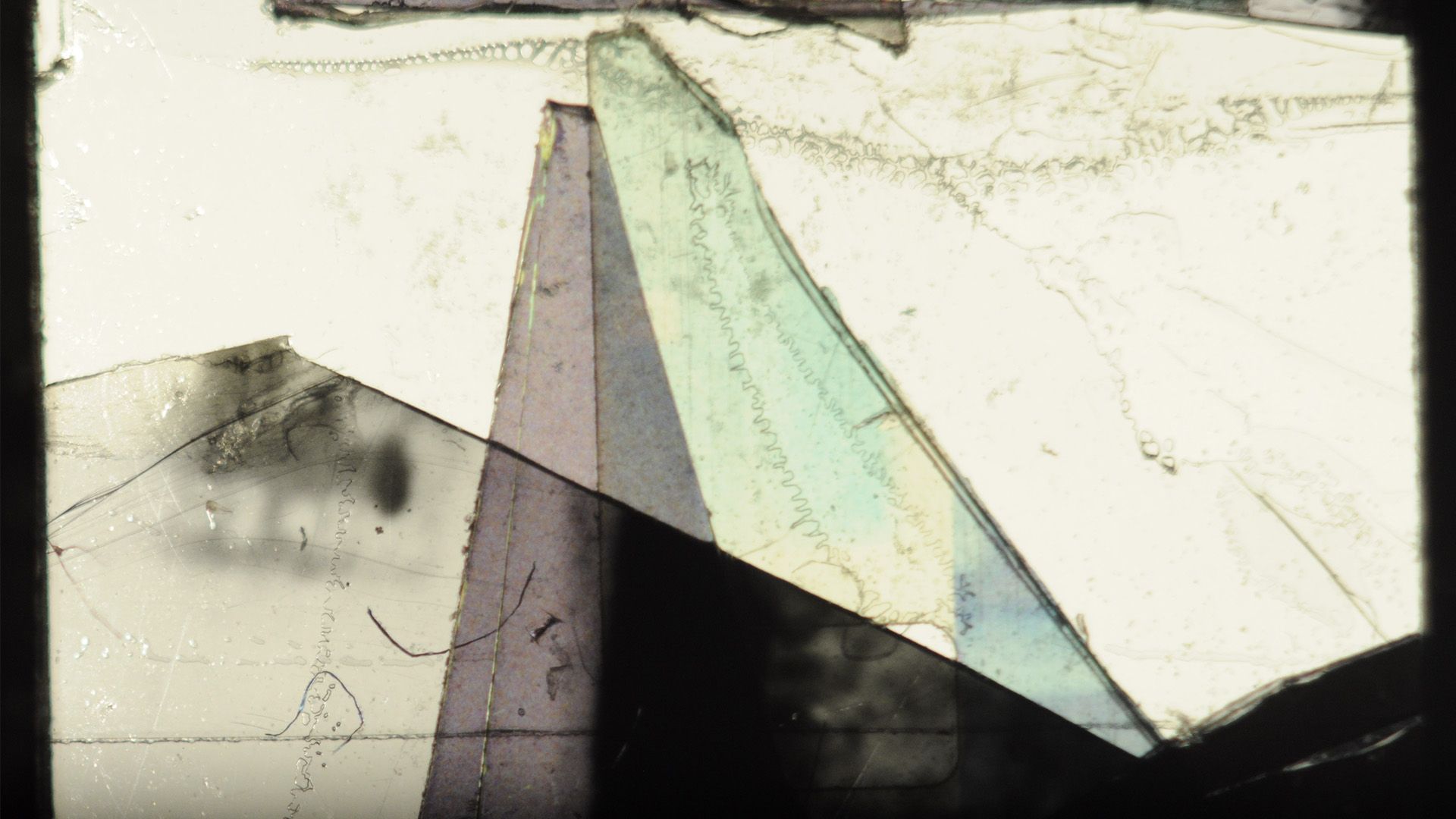

TURIN

Rhayne Vermette | 2015 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 7 min

Fetishized alpine landscapes of 16mm film collage and rayograms generate an obscured portrait of the godlike, Carlo Mollino. Completed in anticipation of a personal pilgrimage to Turin – this film delineates what is at stake for the genius bachelor architect as well as the deplorable, unremittingly heartbroken filmmaker (who adores him so). (Rhayne Vermette)

DOMUS

Rhayne Vermette | 2017 | Canada | 16 mm to HD | 15 min

“The block of marble is the most beautiful of all statues” – Carlo Mollino

This is the story of the godlike architect, Carlo Mollino, animated within the desk space of failed architect, Rhayne Vermette. Made, with love on 16mm, 35 and Super 8, this classic tale of Pygmalion investigates intersections between cinema and architecture.

For E. Ackerman, A. Jarnow, and T. Ito. (Rhayne Vermette)

RHAYNE VERMETTE

BUILDING A HOUSE

A house is not necessarily a home, but in the collective imagination one thing gets identified with the other. The spaces that have been inhabited but which now only exist as ruins, the ones that exist here and now, and the houses that potentially may be built are all, in a way, the theme of almost all of Rhayne Vermette’s films. From her film collages and animated films to her fiction Ste. Anne, projects of very different calibres, this idea gradually changes and develops based on the same process for creating each shot, each brick-fragment that will go on to form the whole.

There is some biographical information that is of interest when delving into Vermette’s work. One is her origins: Vermette was born in a rural town in Manitoba, a central province of Canada with a climate of extreme cold in winter and stifling heat in summer, and with a particular landscape and idiosyncrasy. The most important town in the province is Winnipeg (Guy Maddin’s hometown and home to The Winnipeg Film Group, with which Vermette has maintained a close but critical relationship). Vermette, who vehemently states that she will never leave Manitoba, belongs to the indigenous Métis people, an independent ethnic group recognised since the 18th century resulting from the encounters between First Nation women with British and French-Canadian employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company (here the colonists’ imagery comes up against the more sordid side of colonisation). In other words, it is a complex and also fragmentary identity. The third fact to take into account is that Vermette studied Architecture, a discipline that she left at one point to dedicate herself to film. Her first approach to cinema was through animation and collage (because of the miracles that can be worked thanks to these techniques); in a way, like someone who builds models of impossible houses on strips of celluloid. Finally, Vermette repeatedly affirms that the person who has taught her the most important things about editing is Madlib, a Californian MC and DJ, based on the idea of sampling.

Having said that, the first programme we are dedicating to her focuses on the period beginning in 2012 with her first films, and ends with the amazing Domus (very rightly dedicated to the magician-animators Ed Ackerman, Al Jarnow and Takashi Ito). In this programme there are collage exercises in which she uses a Stanley knife profusely to cut up different fragments of found footage so as to later reconstruct something completely different, as in the case of Tricks are for Kiddo and Black Rectangle. In Full of Fire, this keenness for plastic and construction turns its gaze to a burning building, a home that is dissolving and which it is not possible to return to, in an exhaustive reassembly in which both the images printed on the film and the material itself are the protagonists. Extraits d’une famille and Les chassis de Lourdes deal with the architectural space where the foundational events of any person’s life occur: the banal domestic interiors, kitchens and living rooms that are repeated ad nauseum in working-class homes around the world. The idea of where and how one lives lies behind these films that have something of a family exorcism about them and are closer to an essay in tone, while not losing the impulse to work on collage, manipulation by hand, and animation. Turin and Domus are two different approaches to the work of Carlo Mollino, an Italian architect, designer, photographer and writer, lover of aerodynamics, skiing and racing cars, and an exciting character from the 50s whose vital idealism can be condensed into a famous quote: “Everything is permissible as long as it is fantastic.” In her years as an Architecture student, Vermette found the mould for her work in Mollino’s ideas. Turin, populated by triangular shapes (a minimalist representation of a house, or an alpine mountain), is in Mollino’s words an abstract portrait of the character created by cutting, gluing and scratching celluloid, and using the rayography technique (lest we forget, invented by Man Ray). Domus takes us through the history of Mollino based on his novel Vita di Oberon, where he tells the life of a young architect who has just died, a copy of himself in an autobiography of events that have not yet occurred, which also functions as a manifesto of his ideas. The film is both an architectural projection and a multifaceted animation, like a Russian doll, of Vermette’s own workspace, of her animation and cutting table, of the studio space that architects and filmmakers alike inhabit in the long and lonely hours spent building worlds made to measure.

Vermette changes tack towards new cinematic terrain in Ste. Anne, a fiction feature film that occupies the second programme. The house, and also the vacant land where the protagonist plans a future home, are part of the film’s backbone: the house where she cannot stay, and the one that only exists in one’s imagination. In a way, the past and the future merge. The film, starring Vermette herself and several members of her family, is a charming, mysterious vision of rural Manitoba throughout the seasons, and the colours that they paint in the film. It is also a vision of the people who inhabit it, in an ancestral search ranging from community meetings and in solitude with the women of her town, to the search for what has already disappeared in the photo albums that Renée, the protagonist, flips through over and over again. The fragmentary nature of Ste. Anne is at its heart and at the foundation of its construction, being another materialisation of Vermette’s collage-driven spirit, with different formal codes. One can see Ste. Anne as one more way for Vermette to take root in her own territory, to attempt to explain what makes up that resilient magnetism of Manitoba. And one can also think of it as an intangible way of building a house on that wasteland of one’s ancestors, an intangible house that no fire or mishap can destroy.

Elena Duque