MORGAN FISHER

PROGRAMME 2

Filmoteca de Galicia | Friday June 7th | 7:30 pm | Free entry to all venues until full capacity. It will not be possible to enter the venues after the screening has started.

PROJECTION INSTRUCTIONS

Morgan Fisher | 1976 | USA | 16 mm | 4 min

Regrettably, the labour of projectionists is usually only considered by the audience when they ‘screw up’. This film offers an alternative opportunity.

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

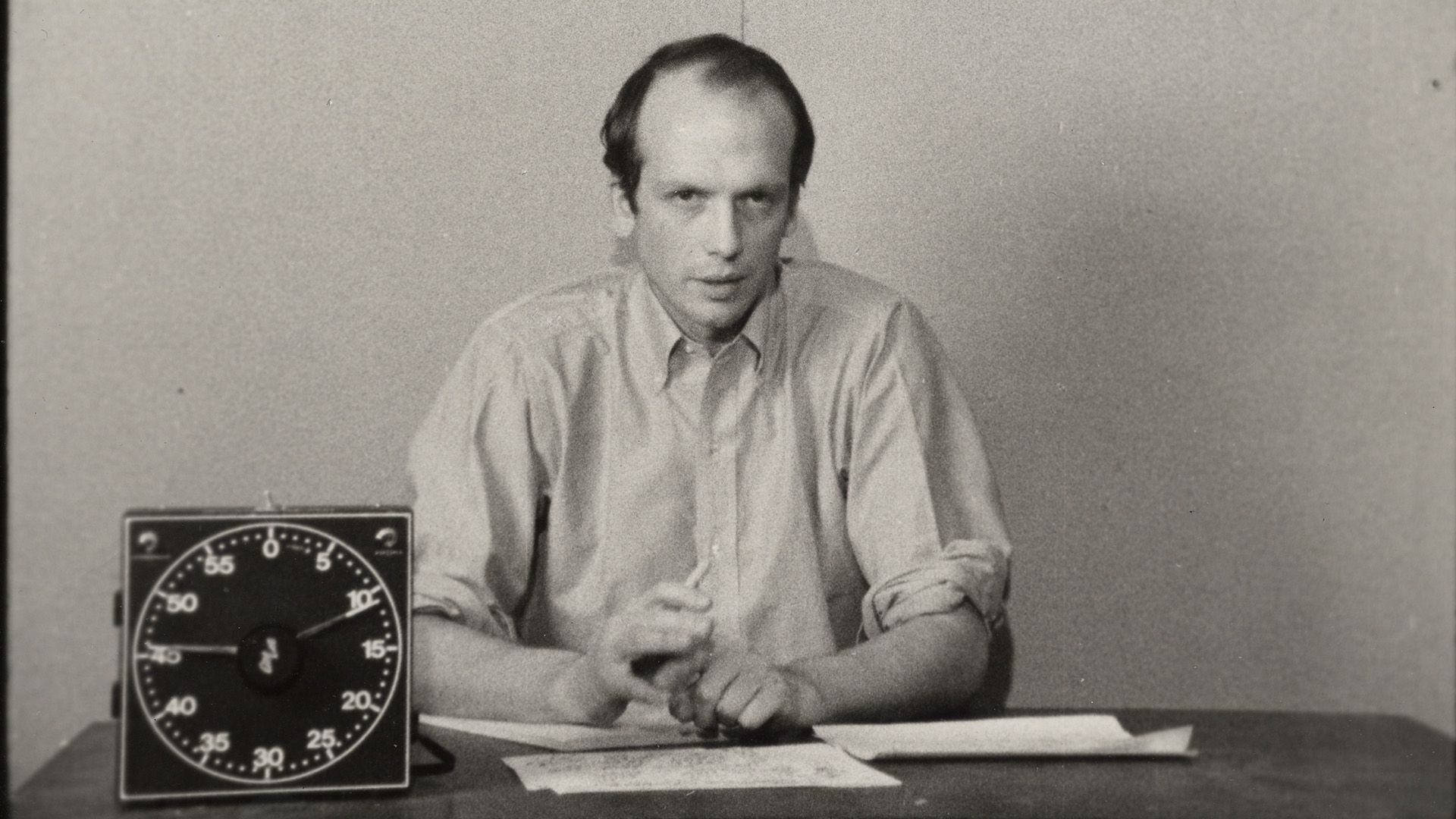

PICTURE AND SOUND RUSHES

Morgan Fisher | 1974 | USA | 16 mm | 11 mi

In a static medium shot a narrator seated at a table delivers an explanation of the combinations and permutations which the sound and picture elements of the conventional monochromatic sound motion picture afford, as the film itself undergoes them.

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

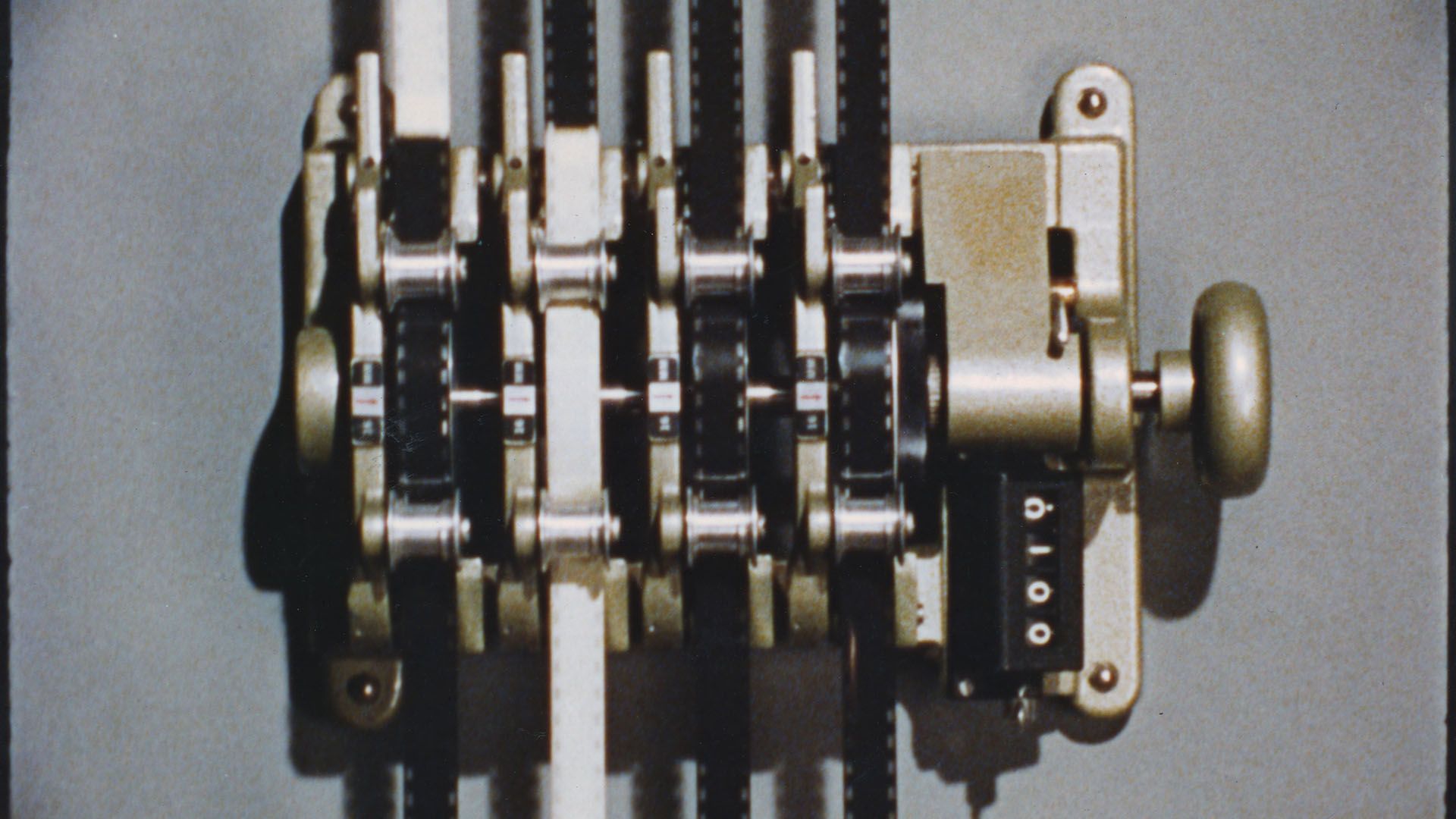

CUE ROLLS

Morgan Fisher | 1974 | USA | 16 mm | 6 min

Cue Rolls suggests that the particularity of cinema is its interface of rigorous mechanical equipment and fallible human process, which is dramatised by the juxtaposition of the precision mechanics of the visuals and Fisher’s somewhat halting narration.

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

PHI PHENOMENON

Morgan Fisher | 1968 | USA | 16 mm | 11 min

Phi Phenomenon is a shot of a classroom clock. The film lasts eleven minutes, and the camera is immobile. I did not want there to be any evident motion in the shot, so I removed the second hand from the clock. But even if we don’t see any motion from one instant to the next, we know that motion is occurring: as the film progresses, we see that the minute hand is no longer where we saw it before. The minute hand has to have moved, even if we didn’t actually see it move.

The film recapitulates an experience we know from daily life. We know that the hands of a clock move, but they move only when we are not looking at them; when we look at the hands of a clock, they appear to be stationary. Phi Phenomenon plays on this contradiction, that we know time is ceaselessly passing, yet when we look at the device whose purpose is to tell us the moment where we happen to be in this ceaseless flow, time stands still. (Morgan Fisher)

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

240x

Morgan Fisher | 1974 | USA | 16 mm | 17 min

In the sync sound footage of 240x (1974) Fisher is seen making photocopies of a black pattern (the design of Maltese cross movement, a part which produces the intermittent motion of the pull-down in a film projector.) Fisher punches holes in the copies so that the images can be properly registered. He then shoots the 240 individual sheets on an Oxberry animation camera. The title refers to these sheets in two ways: “240x” may mean 240 times or (in animator’s shorthand) 240 frames. The film ends with a ten second coda, the 240 frames of animated footage that is the product of the work previously represented.

(William E. Jones, “Morgan Fisher: An Impersonal Autobiography”)

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

DOCUMENTARY FOOTAGE

Morgan Fisher | 1968 | USA | 16 mm | 11 min

Naturalness willfully corrupted by inevitable self-consciousness, unwittingly corrupted by unavoidable naturalness, a role played with incredible nuance and complexity by Maurine Connor.

Print courtesy of the Morgan Fisher Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

MORGAN FISHER

YOU ARE WATCHING A MOVIE

When most people say “movie,” they usually have something very specific in mind. A “short” or a “documentary”, in such a line of thinking, are not “movies”, because a movie can only be a fictional feature-length film. Likewise, when one says “cinema”, one thinks of the venue where we go to watch movies with a box of popcorn in our lap. And, if we had to turn those words (movie, cinema) into a graphic cliché, we would have the silhouette of a cinema camera, a director’s chair (one of those folding ones with a canvas seat and back), a film can or a strip of celluloid with its perforations. All of this leads us to a fossilized idea of industrial cinema, and to Hollywood’s ways of doing things, which in turn are also propagated through books and treatises that show us standardized, univocal ways of writing a script, of planning a scene with its axes and match cuts, set lighting, etc.

In a way, Morgan Fisher (Washington DC, 1942) is the missing link between that Hollywood idea of films and experimental cinema, thanks to a series of works that intelligently break down the conventions of industrial cinema with humour, in a line of conceptual thought that smacks of avant-garde. Most of Fisher’s films are true meta-cinema, films that say “You’re watching a movie,” and the movie you’re watching is about making a movie that has been emptied of any content other than just that. Fisher’s films have been called “structural cinema” due to their material approach to cinema, but the truth is that this idea is not entirely correct, since his interest is directed more towards conventional procedures, which in the years when he began working in the late sixties inevitably involved working with celluloid, projectors, synchronization methods, cameras and other paraphernalia (which, curiously, all continues to graphically represent cinema). Each film is a carefully thought-out system, where the ultimate decisions are taken by industrial standards: the duration of the film reels, the apparatus most often used, the regulated procedures, and the predetermined categories. Fisher, who is also a painter and adapts this way of doing things to painting, has expressed his closeness to Duchamp and the ready-made, and in a certain way what he does in his cinema is to place that industrially manufactured object in front of our eyes so that what is important in the work is not the work itself but the gesture it proclaims.

The two programmes we are dedicating to Fisher’s work do not follow a strict chronological order in his filmography. Programme 1 focuses on Fisher’s oblique look at everything behind and to the sides of Hollywood films, Fisher’s films being placed in order according to what would be the order of production for a film. We begin with the preparatory phases of a film in The Director and His Actor Look at Footage Showing Preparations for an Unmade Film (2), moving on to films that allude to the filming: Production Stills is a film that consists of documenting its own filming, and Production Footage shows us how a roll of film is loaded before shooting, and how it is unloaded when it is over in a twofold play of perspectives that we recognize from the cameras filming and being filmed. The length of these films, or of their parts, is determined by the length of the reels of film, expressing Fisher’s love of standards. Editing, the next phase in producing a film, is expressed here in films such as Standard Gauge, in which Fisher traces out a kind of autobiography linked to industrial assembly procedures (a sphere in which he worked in the sixties), based on their leftovers, clippings and waste material. It is, in turn, a story of 35 mm film, the standard format in industrial cinema, narrated in a single 16 mm shot in which we literally see the strip of celluloid. Finally, also alluding to editing and a certain side of commercial cinema practices, () is composed of “inserts”, close-up shots of objects and actions made to streamline the montage, and which were normally shot by assistants (residual processes that allude, again, to those sidelines and backrooms of film productions). The found footage that we saw in its materiality in Standard Gauge fills the screen here, with what was almost always conceived as filler now making up the main material of the film we are seeing.

The second programme delves into processes involving the technical side and which refer to operating machines in cinema. To begin with, Projection Instructions makes us aware of the existence of a projector and a projectionist thanks to a series of instructions and gestures that turn the projectionist into the protagonist. Picture and Sound Rushes deals with the sound and the usual sound recording procedures (whether synchronized or not) in the industry. Cue Rolls shows us a close-up of a film synchronizer, a device used to convey a set of instructions to the person who cuts the negative so as to assemble the final copies of a film in cinema. Phi Phenomenon alludes to operating the camera and the projector, via the foundation of cinema: the Phi phenomenon, an optical illusion of our brain that makes us perceive apparent continuous movement when there is a succession of static images. Here, it is here humorously shown with a static shot of a watch in which the minute hand is moving so slowly that we cannot really “see” that movement. Then 240x refers to a part of the projector, the Maltese cross, which causes the intermittent movement of the film drive. In this case, we see Fisher throughout the process of producing a film with this matter, breaking down and re-animating his “subject.” This idea of devices at work can be seen more obliquely in Documentary Footage, through the recorder that appears in the film along with a woman. The title, “documentary footage” returns again to self-referencing: not only does the film play with one of the canonical codes of documentaries, the interview, but it uses a continual shot to faithfully document Fisher’s premise or score so as to establish a dialogue between the machine and the performer, between the immediate past and the future, between the being and the record of it recorded.

Elena Duque