NARCISA HIRSCH

PROGRAMME 3 | THERE ARE FEW WHO KNOW THE SECRET OF LOVE

Filmoteca de Galicia | Tuesday June 4th | 5:30 pm | Free entry to all venues until full capacity. It will not be possible to enter the venues after the screening has started

ANDREA 1973

Narcisa Hirsch | 1973 | Argentina | 16 mm to HD | 10 min

Film letter from Narcisa Hirsch to her daughter, Andrea Hirsch, for her 21st birthday.

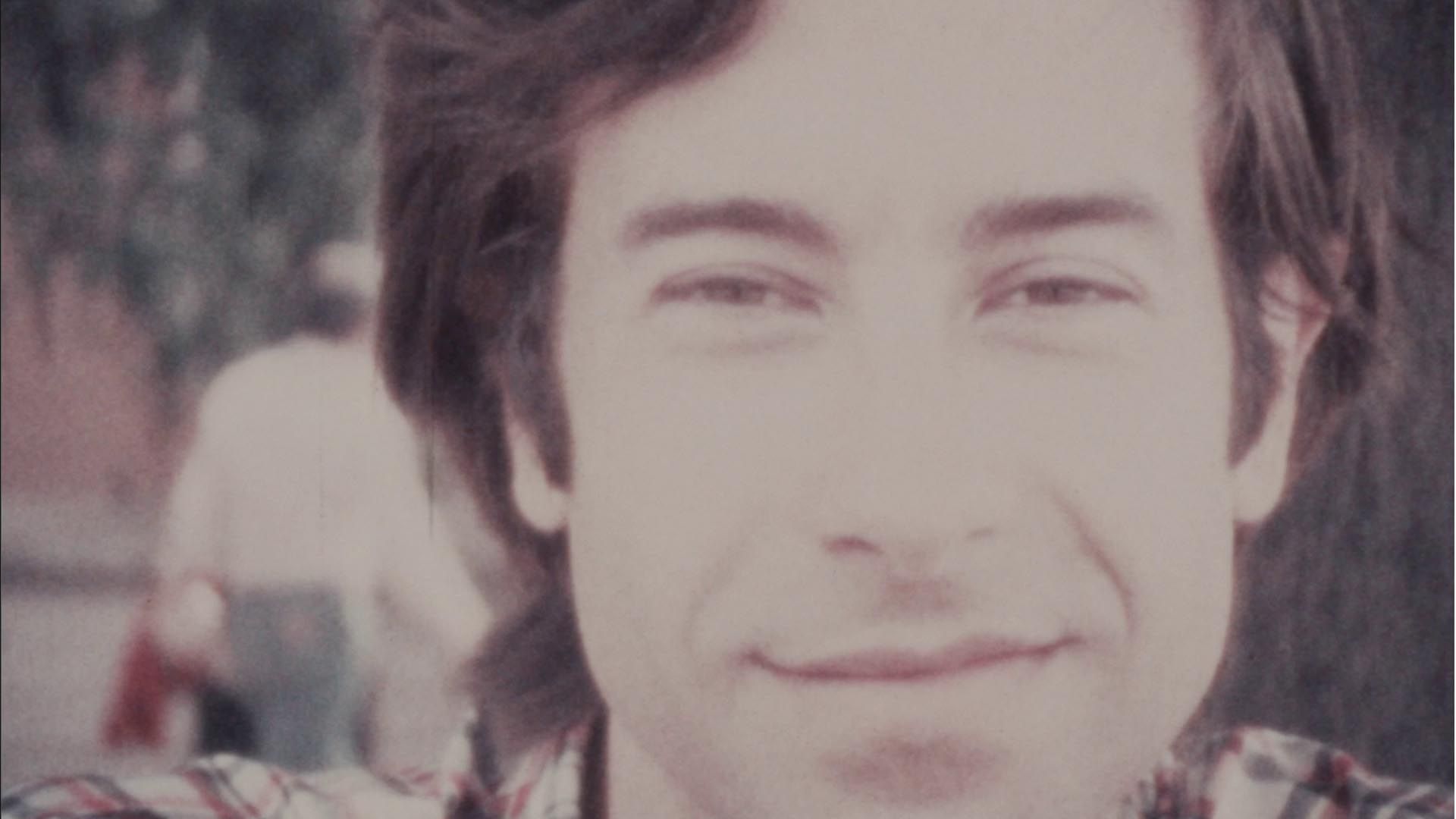

RAFAEL 1975

Narcisa Hirsch | 1975 | Argentina | Super 8 to HD | 11 min

A complex, staggered declaration of love from Narcisa Hirsch to Rafael Maino. A portrait with a sensual, warm gaze: the one from the camera, and the one returned by Rafael himself.

ORFEO Y EURÍDICE

Narcisa Hirsch | 1976 | Argentina | Super 8 to HD | 12 min

Over the music of Orpheus and Euridice by the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck, one can see images of Rafael Maino and Narcisa Hirsch on their travels through Patagonia. (Narcisa Hirsch Filmoteca)

THERE ARE FEW WHO KNOW THE SECRET OF LOVE V3.

Narcisa Hirsch | 1976 | Argentina | Super 8 to HD | 7 min

One of the three scenes in which everyday moments of a couple’s life together blend with the reading of the fiery German romantic poem The Secret of Love by Novalis. It combines the banality of routine with the overwhelming transitory madness of falling in love, the only possible path to love and at the same time the most difficult one.

CAPRICORN 78

Narcisa Hirsch | 1978 | Argentina | Super 8 to HD | 20 min

Narcisa Hirsch was born on 16 January under the sign of Capricorn. These diaries labelled Capricorn 78 show an approach to everyday life with unusual tenderness and beauty: a baby bird that a child lovingly cares for; a calf being born; cats and dogs; a house in the snow; a fire; Narcisa on the grass; Narcisa swimming; a full life.

RAFAEL, AUGUST 1984

Narcisa Hirsch | 1984 | Argentina | Super 8 to HD | 12 min

“I was very happy with you, and now the reeds bow over the waters. There is no nostalgia.” On Rafael Maino’s birthday, Hirsch creates a letter-film using images they shot together in Patagonia and travelling through Chile and Brazil, as well as images of bodies (above all male ones) that she thought he would be attracted to. The soundtrack shows Hirsch reflecting on their tumultuous relationship over seven years. Rafael, August 1984, is part of a special universe in Hirsch’s filmography, along with Raphael 1975 and Orpheus and Eurydice. (Cecilia Barrionuevo, Viennale 2023 Catalogue)

NARCISA HIRSCH

PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST AS A HUMAN BEING

To say that Narcisa Hirsch (Germany, 1928 – Bariloche, 2024) was one of the most important artists in Latin America—and the world—is a statement as true as it is incomplete, a cliché of this system of hierarchies and standards of genius seen through patriarchal rationale. More words are needed to describe her fairly. Narcisa Hirsch was a person brimming over with creativity: she began as a painter, then followed the revolutionary paths of art in the 60s, ending up in the happenings, and then from the recordings she made of those happenings she began making films. Her encounter with North American experimental cinema opened up to her new formal adventures typical of the medium, and during the seventies she made several historical films within the powerful Argentine experimental cinema scene. From the late seventies and eighties, she devoted herself to a cinema of lyrical forms approaching the mythological and philosophical at times. She also experimented with fiction, and after a few years’ pause, she returned to cinema via the medium of video. Beyond her résumé, there are more things that can be said about Narcisa that go a step beyond her career as an artist, expanding the field to her essence as a human being. She was an important unifying element for the Buenos Aires scene, not only with her contemporaries in art (Marie Louise Alemann, Walther Mejía) and the somewhat younger generation from experimental cinema (Claudio Caldini, Jorge Honik, Horacio Vallereggio, Silvestre Byron) around the Goethe Institute and the Di Tella Institute. Even in her elderly life, she was one of the new generations (Azucena Losana, Pablo Marín, Pablo Mazzolo, Tomás Rautenstrauch, Federico Windhausen, Benjamín Ellenberger). In addition to this desire to create community, she also had a tireless curiosity and an unprejudiced openness to what was around her. All of her work is permeated by joy and play, sometimes by a manifest sense of humour, and always by the desire to experiment with form, to attempt everything and to commit herself to everything she did. To look closer at the figure of Narcisa Hirsch is to see someone who seemed to live life to the full, who made the most of everything she had, and who, furthermore, dared to do it all as a woman in a man’s world. Taking a closer look at her films means getting to see the artist, but also the human being, in indissoluble and generous coexistence.

Narcisa Hirsch’s work, already wide-ranging and rich considering what we knew, has acquired a new dimension with the work on preservation, digitization and access done by the Narcisa Hirsch Film Archive or Filmoteca (headed by her grandson Tomás Rautenstrauch). With this, her diaries and film letters have also come to light, as well as other notes and sketches—all films originally not intended for public screenings. They are works that, beyond their biographical interest, connect directly with the diary cinema inherited from Mekas and, in the case of the letter-films, with a personal cinema addressed from a perspective rarely seen, attached to vulnerability and openness, to exhibiting the complexity of human feelings and emotional ties. Upon organizing a retrospective of her work (here we have given priority to works on film), it was important to bring that facet to light, attempting to incorporate it organically into all the rest (of which there is a great deal).

The first programme we are dedicating to her is entitled “Patagonian Suite”, as a way to draw attention to the important role of Patagonia and its vast landscape in her work. Located in southern Argentina, Patagonia is a vast, partly wild region, made up of impressive valleys, mountains, steppes, lakes and beaches, and whose most visible city is Bariloche. Hirsch, who divided her time between Buenos Aires, Bariloche and her trips abroad, felt a natural urge to film Patagonia that became diversified in many ways. The session opens with two works that suggest an emotional affiliation with the place: Pradera (Meadow), made with Tomás Rautenstrauch, in which she observes the Patagonian landscape with her grandson from her home in Buenos Aires, opening up a portal that transports us between the two places. The Super 8 reel entitled Bariloche. Fotos ByN (Bariloche. B&W Photos) intersperses family photos and memories with that same landscape. The majesty of the earth in all its breadth is presented to us in Potrero (Paddock), Narcisa’s way of seeing Patagonia even when she is not there. After seeing the place, and understanding the family ties, we move on to see Narcisa’s way of life, the dynamism and creativity of day-to-day life in the Patagonian diaries 2. Then Patagonia and Ulises present us with hallucinating visions of the landscape that acts as a canvas for a psychedelic image made into a film. Patagonia (short version) gives way to a recording closer to ethnography, without losing sight of formal experimentation. Finally, Para Virginia (For Virginia) is a film letter to an absent woman in which we tour the streets of Bariloche (with Narcisa’s famous graffiti, in this case extracts from Virginia’s letters), to end up in a performance representation of the feminine spirit that connects with the following programme.

Under the name (with a humorous nod) Mujeres, hombres y viceversa (Women, Men and Vice Versa), the second programme gathers some of her works that focus most on lyricism and symbolism; films that allude to the feminine and masculine condition in more-or-less veiled ways. From the enigmatic lights and shadows of Señales de vida (Signs of life), a film that at times evokes a hidden threat, we move on to Hirsch’s particular vision of an Amazon myth in Ama-Zona (Ama-Zone). The film La noche bengalí (The Bengali night), made jointly with the German Werner Nekes during his visit to Buenos Aires, seems to indicate the impossibility of an encounter between man and woman in the outside world, in contrast to the warmth of an intimate encounter. A-Dios (GodBye) is a film that examines masculinity and its tropes of conquest and submission through powerful images and quotes, in a film that includes eroticism and also violence. Finally Pink Freud, in a lighter register, looks irreverently at Freudian psychology and the implications surrounding motherhood and, if you will, reproductive rights. Filmed in her studio, a sleeping woman and a man emptying a sack full of little plastic babies (also hinting at one of Hirsch’s street happenings, Muñecos (Dolls), where she gave those same dolls to passers-by, telling them: “Have a baby”).

The third programme is dedicated to diaries and film letters, taking its title from one of the films in it, Pocos son los que conocen el secreto del amor (There are few who know the secret of love). Here we have a letter to her daughter Andrea for her 21st birthday, and several films in which she breaks down her loving relationship with Rafael Maino with unique sincerity and sensuality in vital collages of images sometimes accompanied by her voice. There is also the diary entitled Capricorn 1978, a collection of Super 8 rolls that are especially delicate and attached to textures, to observation of detail and the miracle of life (and death).

The cycle ends with the programme “The artist’s workshop”, which shows some of Hirsch’s best-known works, and also those closest to contemporary art: those related to happenings and with structural cinema, all of them linked in one way or another to her Buenos Aires workshop. In an exercise of temporal comings and goings, the programme begins by introducing us to space in Taller (Workshop), a film that gets the off-screen imagination going: a fixed shot of a corner of the workshop that contains the entire workshop thanks to the voiceover description we hear off-screen. Retrato de una artista como ser humano (Portrait of an artist as a human being) presents us with a kind of small and playful artistic biography in which we see the “making of” of happenings like Marabunta (Rabble) and films like Cancionces Napolitanas (Neapolitan songs), before going on to see those works themselves, in addition to a recording of the Edgardo happening. The feeling of community permeating the workshop inhabited by Narcisa runs through all of these films, as occurs in Testamento y vida interior (Testament and inner life), where she films her studio again and sees herself in a coffin carried by her friends from the streets of Buenos Aires to the snows of Patagonia. The programme closes with Come Out, her key work, a replica of the discovery that Michael Snow’s Wavelength meant for her. A zoom-out (which moves at the same time as the sound work by Steve Reich accompanying it, based on the increasingly accelerated repetition of a phrase) that works like a mirror to the zoom-in of Pradera (Meadow), with which we opened the cycle.

We go out again into the world after Narcisa, but we are no longer the same.

Elena Duque