We reproduce an excerpt from an interview with Rhayne Vermette by Peruvian critic, researcher and programmer José Sarmiento Hinojosa.

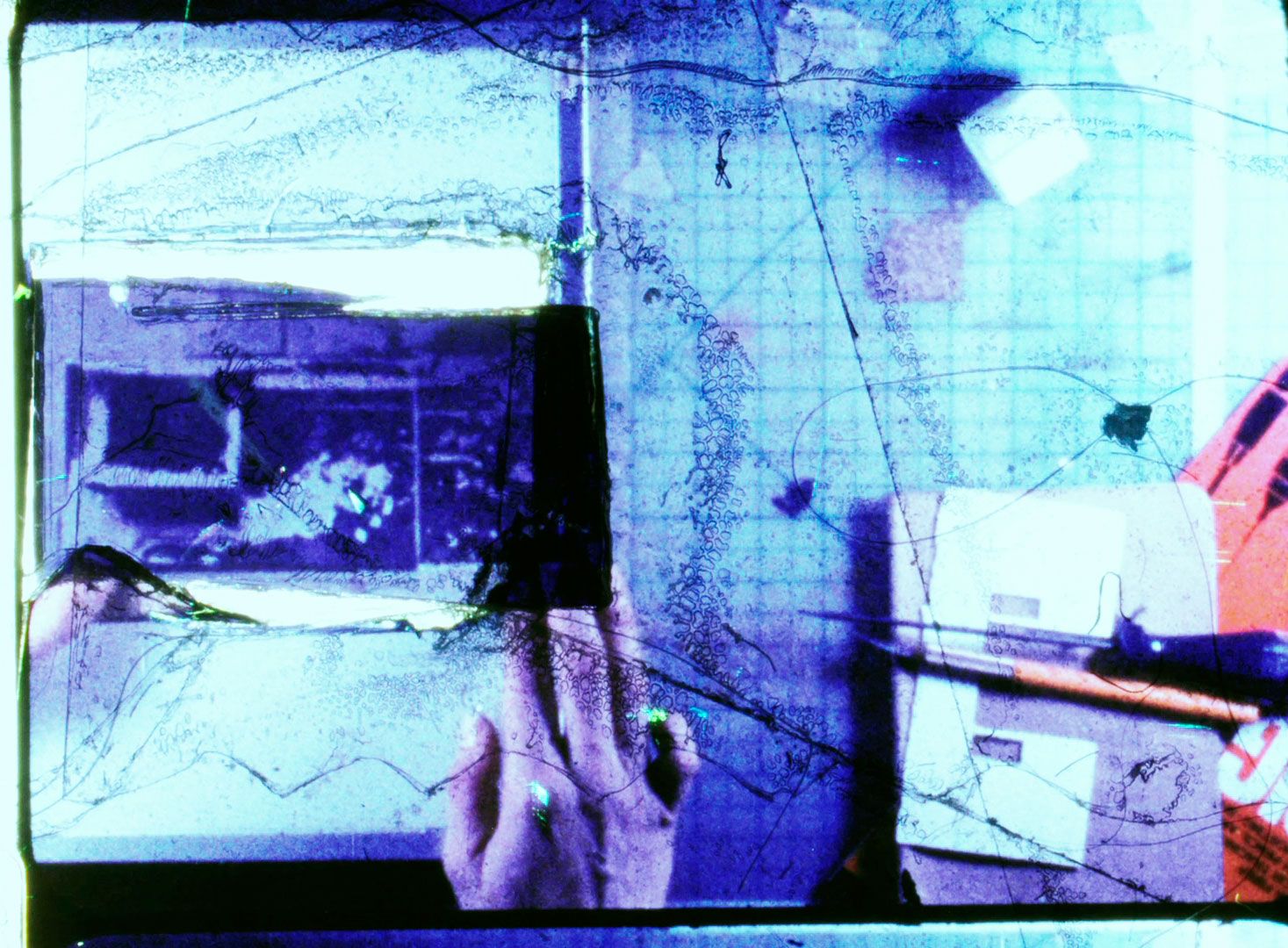

Canadian artist and filmmaker Rhayne Vermette moved out of academia to pursue her own artistic vision. Years later, we’re witnessing one of the most remarkable bodies of work in contemporary experimental cinema. Locked in the concept of the “ruin” and borrowing from contemporary art, architecture and her own process as a filmmaker, Vermette’s works are a unique blend of collage, animation, found footage and recorded images. What follows is a hour-and-a-half conversation with Vermette about her work as a filmmaker, her place as a woman artist in Winnipeg, her influences and other topics.

You’re a self-taught artist; however, your works are incredibly intricate pieces of cinema dealing with themes like architecture and memory, a confluence of animation collage and images which seem to want to recall passages of memory and their relation with space. Can you tell us about the process that made you decide to become an artist and the motives behind your decision?

I studied fine arts for about two years, and I left it. I didn’t enjoy it, there were creepy male professors and all that kind of stuff. But at the time somebody told me the faculty or Architecture here in Manitoba, they were going through some kind of identity crisis, and was kind of working like a conceptual art school, so the logic was like “oh, I can go to that school and learn to make art and then come out and be an architect”. My first three years there were kind of my art instruction, and my introduction to architecture and space, and that’s were a lot of my film ideas come from – these three years which seeded a lifetime of ideas.

But then, each year in March, when the term was about over I needed to come up with a building and I had basically no idea how to make such a proposal. I was interested with things like psychology of space, corporeal built bodies, you know, a lot of metaphysical ideas… such as, for instance, being paranoid somewhere, does that have a consequence to the materiality of the space? So, as a means to try to articulate the things I was most interested in I then started making paper models and animating them. I found the act of animating and making a film was not as painstaking as trying to make architecture. Eventually, I had six months left in my master’s degree and I just took an indefinite leave of absence and I just never went back, I just wanted to make movies basically from that point on. I didn’t know what experimental film was, you know, I had no film experience, I was just really drawn to make really beautiful stills, taking a bunch of them and seeing what would happen if I put them all together. My incision into cinematic space isn’t by way of necessarily thinking in terms of story, or shot lists but rather thinking through materiality of 16mm film, and architectural drawing conventions – plans, elevations, and a heavy fascination on the section cut and its reference to the frame.

As we were investigating your references for this interview, we came upon a quote from architect Carlo Mollino which reads “Everything is permissible as long as it is fantastic.” And this, in my mind, is related so much with your work. Can you tell us about him and the influence he had in your later films?

Yeah, Mollino, this figure was introduced to me, again, in my years at architecture school at a time when I was kind of really coming up against architectural conventions. Wondering and being curious about how those are made and how those can then imply a space’s becoming and inevitably arguing a lot with my studio professors and stuff like that. This particular professor told me “have you heard of Mollino, he’s a bastard much like yourself” so I was like “oh, this guy seems cool”. He was the first person whose spaces I felt really drawn to, I generally feel like I’m really actually naive to architectural beauty but this was the first time I was really drawn to this person and his work. So I kept turning to the many, layered facets of his life which really resonated with me and my own conceptual logic.

His vision of architecture really enlightened that which I was struggling with and continue to struggle with in terms of creation – ideas of architecturally stagnant propositions, and static buildings. I too was primarily interested in questions like … what if there was a way to create something which could transmogrify, most like a shell for its inhabitants. Through studying Mollino, I was able to project romanticized versions of my practice through him, and then DOMUS came out of that – reflecting on this 10-year relationship with this idealized architect who every day worked arduously to try and not only reinvent the wheel, but also challenge it. It was an act of attempting to make a film which sought to make sense of architectural desire and the convergence of cinematic space.

Everything has to be fantastic and I think, for the past four years I’ve been doing this open call for WNDX, which is a local film festival here in Winnipeg, and I think that, in part, DOMUS kind of came out of this grueling task of watching a thousand, two thousand films where you see a lot of work which merely buys into these experimental tropes and aesthetics… which brought into question the practice and state of experimental cinema. I consistently have a longing to be fascinated, to be surprised, to maybe see something presented in a way which has yet to be articulated.. so I use my practice as a means to suffice those very personal and unfulfilled needs and desires.

[…]

DOMUS (2017)

Can you tell us about the myth of Pygmalion and the relation between cinema and architecture in your remarkable film DOMUS?

The Pygmalion thing came from… I think a lot of work that I’ve made prior to DOMUS was a little angst-ridden, especially coming out of doing Les Châssis de Lourdes, which was kind of a crisis film in my personal and artistic practice. I was really wanting to switch gears and put love into something and be loving towards my process, towards what I was making. And then also, Pygmalion also came from Mollino, desire was wrought within the lens of the mirror within everything he made. This also reflects onto my own work, my practice is totally self-indulgent, it’s all about pleasing myself, this kind of eroticism behind the “what is this going to be”. When I undertake a film project, I don’t know… it never ends up being anything that I think it would be and I’ve been enjoying that process of self-discovery and titillating myself and moving things forward. The Pygmalion thing was also turning to my own personal space and seeing where the desire lays within that often insipid space.

For over 10 years I’ve been recording my space, my desk and chronicling these intimate moments but obviously, what’s the drive for that? There must be some kind of drive. So Pygmalion was this way of arcing these drives and also my desire for Mollino,to put him on a pedestal, me kind of disrobing him. I thought it was a really nice metaphor to set the tone for making DOMUS, which celebrates this act of making and the space which surrounds it. Whenever I started working on it, I would put on romantic soul songs and just really tried to get into that loving mood. The process was entirely different from other works, it was awesome.

Domus was a term created by Mollino to describe an unattainable, ideal architecture which could engage both physical properties and abstract concepts – something which behaves and changes with every whim of those who inhabit it … now what if film could aspire to behave this way too? He believed that despite knowing one could never achieve Domus, one could strive for such a state through metaphor … in my film, I am attempting to build with cinema, reflecting on architecture and the act of conceiving of both cinema and architecture, and the intersections of these two as I reflect on my old architectural work and my trajectory as an animator/filmmaker. Through the film I try to represent architecture as a working idea, as an artificial construct, as a physical construct, and even as a working dream – I try to weave all of these together.

FULL OF FIRE (2013)

Full of Fire seems to deal with tragedy, exile (something I’ve also seen in Tudor Village…) drama, tension and disaster. Your animation seems to want to reconstruct or salvage some elements of the lost structures amidst the fire. As the images fade away and become more abstract, we seem to witness a loss, or a faded memory, or the irruption of deconstruction. Can you tell us a bit more about this film?

I had made this film called Take my Word for this Craig Baldwin workshop at the Film Group, where I had used this image of this contemplative looking woman, and then the Film Group had this DIY optical printer with all these LEDs, so some of that firefighter footage came from attempting to use this device – and it failed. Film kept getting stuck in the machine, or it would get jammed so in the end we just took all these film scraps and then shoved them in a black bag and sent it off for processing, but very little came back with images. The film’s clouded colorful images are from that experiment… So these original images of the firefighters and the few optically printed images conjured many ideas surrounding the metaphor of a burning house. I had been sitting on this Three Degree’s soul song monologue for a while now, wanting to make a film from it – and the idea of home and female desire and the confluence of the both started to make sense through this monologue – and finally I had found a voice for the woman from the film Take My Word.

The way I work with a film is not with a Steenbeck, it is kind of this one on one relationship that I have with the physicality of film, understanding what a second LOOKS like, and then thinking about rhythm and music and all that stuff – how can I play within those seconds. Full of Fire is pretty much all hand-spliced through thinking of what sources of found footage I was playing with, and how to create a narrative tension through movements between the various images. The juxtapositions between this image of a woman who often looks off beyond the frame – and how to then with a cut, fill in that void to create various metaphorical ties – is she looking and longing for a firefighter? Is she looking at a burning building? or is she just far from the scene, and the scene perhaps just evocative of her interior world? Obviously while working I was reflecting on my own personal narratives – ideas of being stricken by love, longing for home, longing for someone… I think these are recurrent themes, however it’s the composition, layering, and juxtaposition of images which open these themes up to much broader and more interesting conversations. It was important to me to have the image of a house in the film as a collage – to really impress upon viewers the idea of a metaphysical home – what can this be? While splicing I was also thinking about rhythmic chaos, igniting things, the pop and fizzle of something burning, so I would splice in random frames of vibrant colors, and so on… I only saw the film upon a first transfer, and surprisingly it all kind of worked out.

The soul monologue of the film was interspersed with an actual audio recording of the optical track of the film, and in the end the audio was cut to the transfer of the film. I mean, I made that film in less than 24 hours; it was just a fervent, angry splicing process.