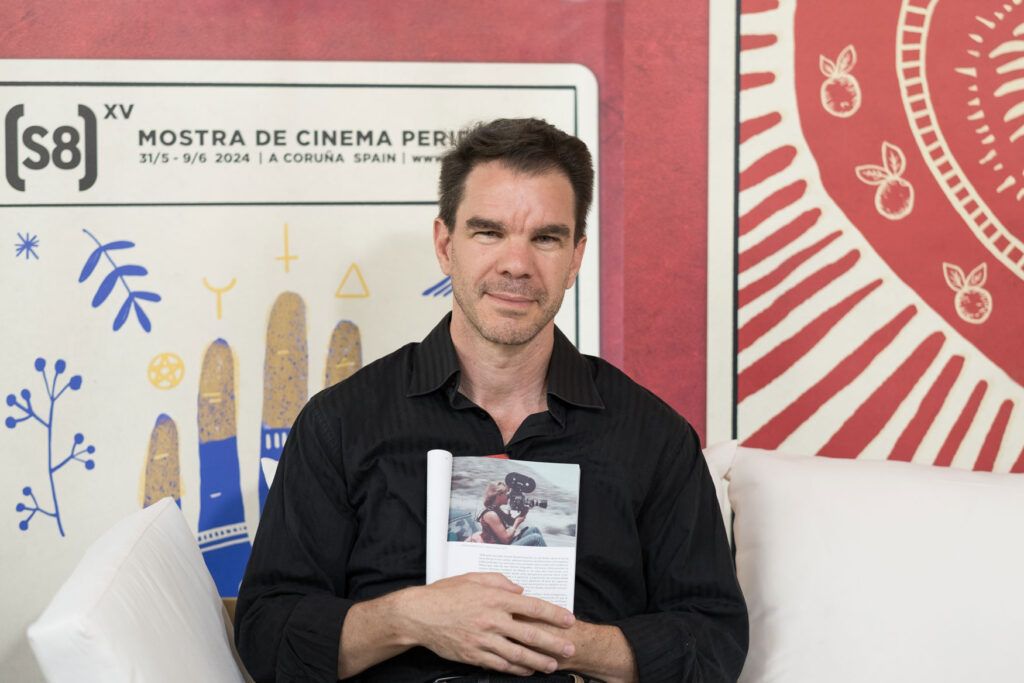

We interviewed Tomás Rautenstrauch, director of the Narcisa Hirsch Film Archive or Filmoteca, about the recent work to preserve and discover films by this free, vital filmmaker.

Right now you are very involved in the work of the Narcisa Hirsch Film Archive or Filmoteca. What is your personal relationship with her work?

I’ve always been committed to her work, because in addition to being the director of the Narcisa Hirsch film archive, I’m her grandson. I went to Narcisa’s shoots, which were her with a camera and a friend who filmed. It had happened since I was a child; she always took me. I was at the shootings of many of the films we are going to see at this festival. And then I was also very much influenced by her way of looking at the world, and at some point I started studying film, and then I left Argentina and worked in more traditional film and television production. When that ended, I returned to Argentina and my origins, to a more artistic, freer cinema. And that was when we began to think together with Narcisa, or rather Narcisa together with me, about what was going to happen to her films. She didn’t want her physical films to be distributed with a few here, a few there, so we set up this foundation. It’s a physical space where her films can be preserved in the best possible way. Then she won an award, which she donated to be able to build the storage room and library for the Narcisa Hirsch Film Archive. Towards the end, they gave me a grant to scan all these films in the US, in Los Angeles, in a fantastic laboratory. And thanks to that, we can watch the movies today with the quality we can see, and discover the “new” movies that are appearing.

Was there a specific moment when the Film Archive was founded?

There wasn’t a founding moment, but several, because the idea was moving backwards and forwards at the same time. First, an institution appeared in the US, but she wanted her films to remain physically in Argentina. Then a foundation appeared in Buenos Aires that was willing to take the films, but that didn’t work either because they were people who didn’t know about cinema or experimental cinema. And then the idea arose that Narcisa would donate the films to the Cinema Museum in Buenos Aires. But that wasn’t ideal either, because even though it’s an institution that works quite well and its director does everything possible for that to happen, it’s an institution that depends on the approval of the government in power, so sometimes there’s money and sometimes there isn’t, and Narcisa feared for the continuity of that over time. Narcisa had a very small apartment that she rented to get a small income. She vacated it and we set up the library there. What had been the bedroom got converted into a storage room, and the living room was transformed into a library, screening room and workplace. And at the beginning of that process of ideas that came and went, first there was a small group with whom we met with Narcisa to watch movies, which included Cecilia Barrionuevo, Federico Windhausen, Rubén Guzmán and Daniela Mutis—who was also quite important because she was Narcisa’s assistant in the later years, Pablo Marín and Pablo Mazzolo. That was the more-or-less experimental film group that accompanied Narcisa and it was the first group that was involved in the Filmoteca with an amorphous idea of what it was going to be, because at first it was going to be a place to give workshops or classes, and then it gradually found its own direction by itself. The group gradually dispersed, but the Filmoteca is a physical place that requires care and a physical presence in Buenos Aires. So finally I was in charge of the Filmoteca and now there is also Lucía Ciruelos, who accompanied us in the last year-and-a-half working on the archival and restoration side.

The work of the Filmoteca or Film Archive has also involved bringing to light works by Narcisa that were not originally intended for public exhibition, but which have finally ended up being shown. Can you tell us about that process of deciding to scan certain materials and also show them as films?

Yes; that was also a process that had a life of its own, because Narcisa’s films were very poorly preserved. She kept her movies in a wooden cabinet in her house, which was not the best place to keep them. They were there for 40 years, withstanding Buenos Aires’ temperatures of great heat in summer and the cold in winter, etc. What’s more, most of Narcisa’s films are single copies. There are copies that she used to make different montage versions, but the films she projected were basically one copy, so the vast majority were very fragile. When we put together the film archive and we were doing an inventory to take the films from her workshop to this apartment, we decided not to project the films themselves anymore. But to do that, we had to scan them so there was a good copy. And at the same time, I decided to start watching everything to see what was there—everything: the separate reels, the discards and the different versions of the films. Narcisa was living in Bariloche and when she came to Buenos Aires we would have sessions. Sometimes Daniela Mutis would also be there, and we would take notes. And there were two situations. One important situation was that at the time we were looking at those films, we were also looking for laboratories to scan them. It’s an expensive job; there’s a laboratory that’s quite good, but it’s very artisanal. And a professor appeared from a university in Los Angeles who was doing research on Narcisa’s films: Erin Graff Zivin. She wanted to see what was not yet digitized at the time but which we had decided not to show, but, well, she insisted and had come from the USA, so we went to Narcisa’s workshop and saw things from that list I had of things to watch with Narcisa. At that time, Narcisa was in Bariloche, so we grabbed three or four reels and projected them. I had never seen those films, and obviously neither had she, but we both said, “This really has to be scanned; we have to get them into distribution.” And that was the start of long months of conversations, emails and WhatsApps between Erin in Los Angeles and myself in Buenos Aires, to see how we could do it. Later, that grant was expanded to include other things. In those months of negotiations, Narcisa came to Buenos Aires and we watched the movies. And I was noting down the films that seemed interesting to me that were not digitized. The ones that were digitized that Narcisa was distributing were the obvious ones—the ones that were going to be re-scanned in better quality. But then there were a lot of films about which Narcisa always said, “That’s nothing; that’s worthless. Nobody’s interested in that; I made that for my friends,” as well ones she completely discarded. I didn’t pay attention to her and we scanned them anyway. Then there were a number of films that had certain errors in production, because they are films made very artisanally. For example, the film Surely Bach closed the door…which was screened last year at (S8), had problems with the soundtrack and some of the women couldn’t be heard, so Narcisa didn’t screen it because firstly, she said no one would be interested, and secondly, I had sound problems, but those problems are solved very easily in digital format. And indeed, it’s a very powerful film that was distributed a great deal. Then there was a series of films that we’re going to see today in the third programme of (S8), which are the letters. The ones about which she said, “Well, that’s something I made for Rafael; it’s a birthday gift for my daughter Andrea,” etc. There’s one of Rafael’s films that’s a birthday gift for him, then there’s a letter for his daughter Andrea, and they were things that Narcisa did not see as worthy for an audience other than Rafael or Andrea. Once they were scanned, we watched Rafael’s films together. Narcisa wanted to see them before they were distributed, and we saw them together in Bariloche with Rafael. She wanted to refresh her memory of what was being said in those letter-films, and in the end she said, “Well, alright, they are OK to be distributed.” Obviously Rafael was also very touched by that and wanted to see them. And we still have to do a session because there are films with Rafael that continue to appear, made with him. And then there are a number of films that I really didn’t see as worthwhile either, but festivals generally ask for other types of images, for catalogues, to make a trailer or whatever. So in that entire package of scans, I decided to include little reels that were discards, which I thought were interesting for such situations. And miraculously, they have been put in the programme. In this festival, there are films in the programme that will be shown for the first time made from these diaries or reels that had been discarded, or reels that had not been shown. So it’s very interesting for me to see how the life of these reels is imposing itself.

In all this side of Narcisa’s cinema that we didn’t know about, I’d like to know what one is your favorite among these new discoveries and why.

I have to say that I keep finding little reels. Surely Bach closed the door…is a film that I think is wonderful and which is becoming one of the most important films in Narcisa’s filmography. That’s quite incredible. And then there’s one that is Orpheus and Eurydice, which is a film that I find very emotive. And there’s another film which is the Rafael letter from ’84. Those are the three films that touch me the most from those that have been scanned so far.

And how did she relate to it; how to show all that material that for her wasn’t part of her work as such?

As I say, there wasn’t a very emotional relationship. She said, “Well, this is worthless; no one will be interested in this.” And then she was surprised above all that Surely Bach closed the door… began to circulate at festivals. She was rather surprised; it was curious why that happened. But I have to say that in the last year Narcisa obviously had an interest in what was happening with her films, and asked how it had gone and where they had been shown. She asked about Ángel and Ana, whom she met when Surely Bach… was screened last year in (S8). But on the other hand, she was very detached from her own success. At one point, Erin Graff Zivin asked her two years ago about the success her films were having and she replied that firstly the success had come too late and secondly that she had never sought that success in her films because if not, she would have made another type of cinema. And that also seems very important to me: that she made absolutely free cinema, and such freedom was also linked to not seeking success in every sense.

At the festival, we’re opening the series with a film that was shot by you and by her, which is Pradera (Meadow). Can you tell us where that film was shot; how that idea came about?

Yes, that movie has two origins. One of them is an image that was re-filmed, which is the image of those little meadows, because she had a big area in Bariloche and decided to make a plantation of oats and different types of grassland for pasture, because in summer there’s the famous Patagonian wind, and she really liked that wind that made the grasses dance; she really liked that motion. And she always asked me to film them, just to have a record of that dancing, so for several summers I filmed that with a video camera. But we never did anything. Then at some point Azucena Losana appeared, who was working in a Super 8 lab in Buenos Aires called Arcoíris. And Arcoíris has, or had at that time, a small contest called “Toma única” (“Single Take”), where they gave away a reel of Super 8 so that one could make a film with no montage, simply with what was being shot on the camera. So she gave Narcisa and me a reel to co-direct a film. And, well, we made that 3-minute movie. The end result was screened only once, and then many years later at (S8) the other day. The room that appears in it is Narcisa’s workshop, where she kept the films and where, when she came from Bariloche to Buenos Aires, the group I was talking about before would meet. It was her house; we would get together for dinner with a group of filmmakers, and after dinner we’d go up to the workshop to watch movies. Sometimes they were films brought by friends coming back from a trip; sometimes they were filmmakers who were visiting who showed their films. Other times it was Narcisa’s films, from her collection, when those famous cabinet doors in that workshop opened. You can see the screen itself, which dropped down in front of the film library, and Narcisa can be seen sitting down. I like that film a lot because you can see Narcisa sitting in the place where she would sit to watch those screenings. After the screenings, we would go back down to the kitchen to have ice cream and talk about what we had seen. Those were our meetings. The ice cream was very important.

There are several things. It’s Narcisa giving me the reel and the camera. And then there’s the re-filming, echoing what she always did by re-filming. And there’s also an echo of the zoom in Narcisa’s films; there’s a zoom that ends in those little grasslands that are like a nothingness.