- ’TORTUGA [pasaje cromático 4]’, by Brenda Boyer was the project chosen in the last invitation from BAICC, the International Artistic Residency for Cinematographic Creation promoted by (S8) together with AC/E and LIFT. In September 2024, Brenda travelled to Toronto to work at the LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) facilities and to shoot in Toronto’s urban parks, implementing the principles of chromatic separation and constructing a film in which the natural environment vibrates through light, opening up a space of mystery within. We talked with her about it all and the treasures she has found in her chromatic walk. The film performance resulting from this residency can be seen in A Coruña next June at the 16th (S8).

—Could you give a short introduction to your project “TORTUGA [chromatic passage 4]”? What is the background to it?

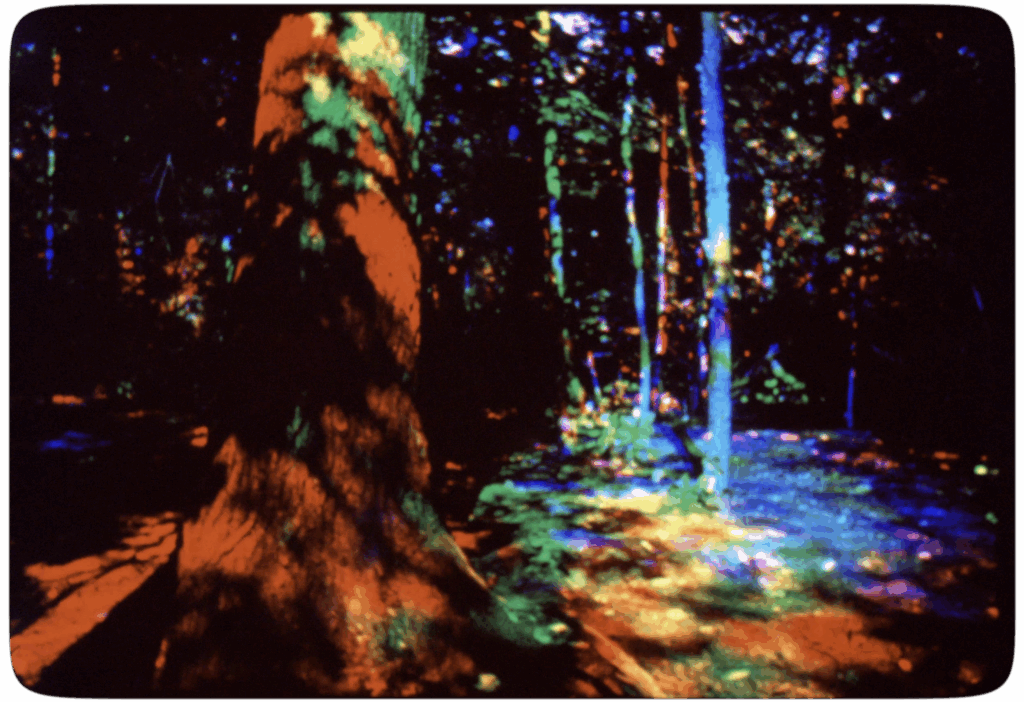

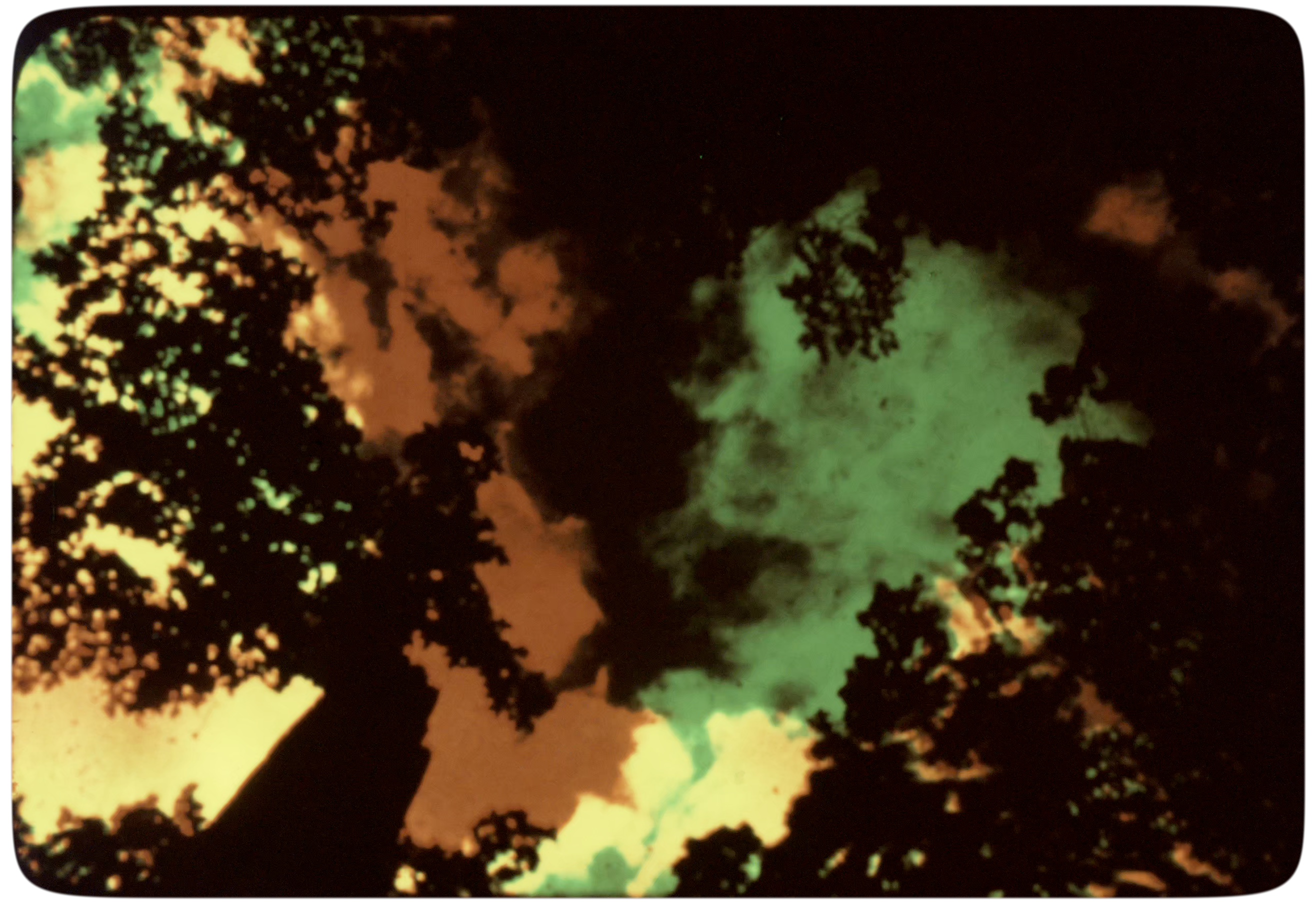

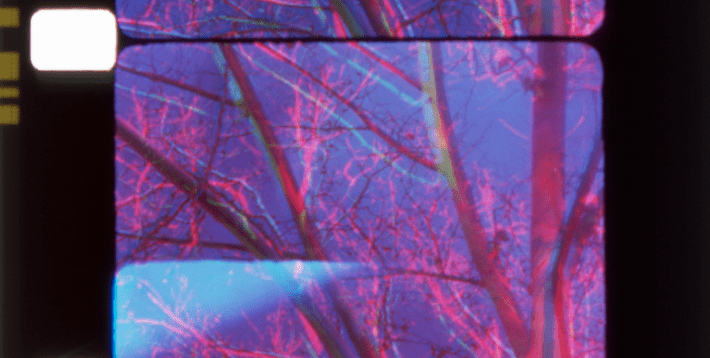

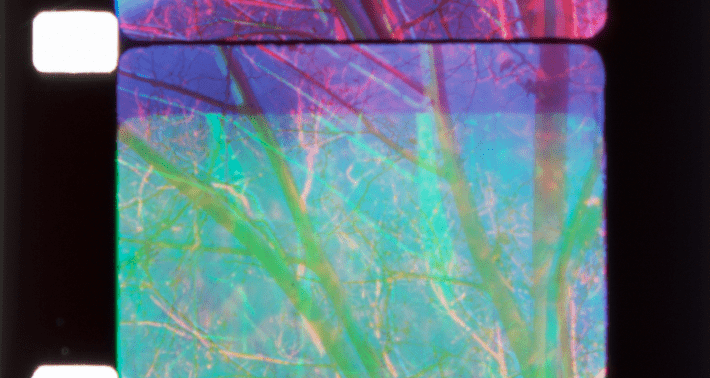

Turtle (Tortuga) is the fourth chromatic passage in a series of experiments that I began with my partner and artist Beatriz Higón, with the intention of seeing what would happen by filming three times—each time with a different green, red or blue filter—with objects, spaces or landscapes lit by sunlight at three different times and shaded mostly by organic patterns of trees, branches and leaves, rocked by the wind, and discarding the idea of playing with the motion of entire volumes within the shot.

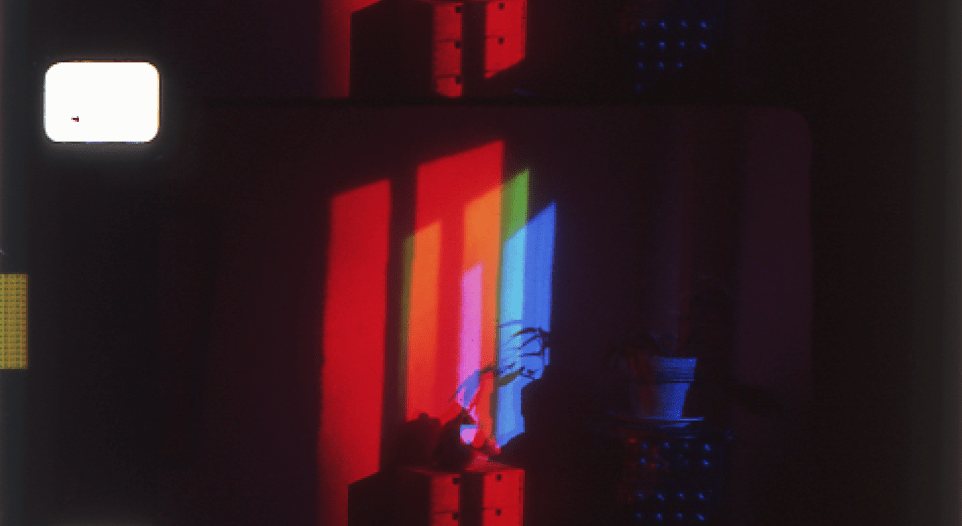

This intention came about after seeing Viktoria Schmidt’s work NY RGB, and the first image in that series resonates directly with this film: sunlight silhouetted by a window projected onto the inside of a house, but in our case the house isn’t in New York. And that’s important, because it represents both a clear similarity yet a clear distancing from that piece. From there on, the resonances faded; we were seduced by the forest.

—What did it mean for Turtle to be able to count on LIF’s technical equipment?

We began to investigate superimposing directly in-camera with ektachrome, so any playing with the layers of colour had to be done with a variable shutter, paying close attention to the Bolex frame counter. The conclusions drawn from playing a little with opening and closing layers, fluctuations in light intensity and variations in filming modes (frame by frame, in bursts or continuously) all pointed to the possibility of “animating” (in a more magical than literal sense) the forest, the surfaces and the spaces.

For Turtle I decided to explore this avenue further. To do so, having an optical printer opened up a new world of possibilities that were impossible to do in-camera, and it meant a change in methodology to be explored.

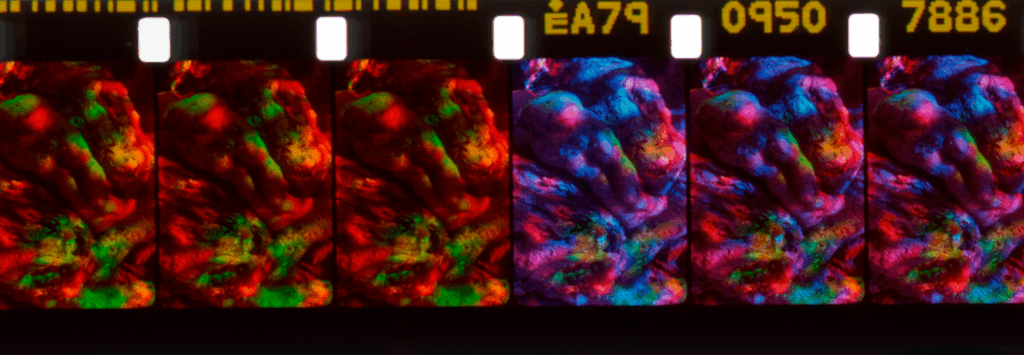

On the one hand, instead of superimposing in-camera on colour film, I started to film “the same” shot three times separately in black and white, but each time with a different RGB filter. The idea was to extend that material in the copying in colour and to play with repetition. Keep in mind that in the black and white footage I had about 100 frames per layer, but in the colour copy I extended this footage to 1080 frames.

On the other hand, on being able to control the frame rate during copying, as well as the light intensity and the RGB layers appearing, and to do so with frame-by-frame accuracy, this opened up the possibility of composing rhythmically and of playing with different layers of time.

—What do you mean by layers of time?

By layers of time I mean that I could slow down or speed up the pace within the image, but also the speed of the variation in the colour changes and, yet another layer: in the flickering of the image, including black frames.

—It seems that the method became increasingly structural. Tell us briefly about the creation process during your stay at LIFT in Toronto.

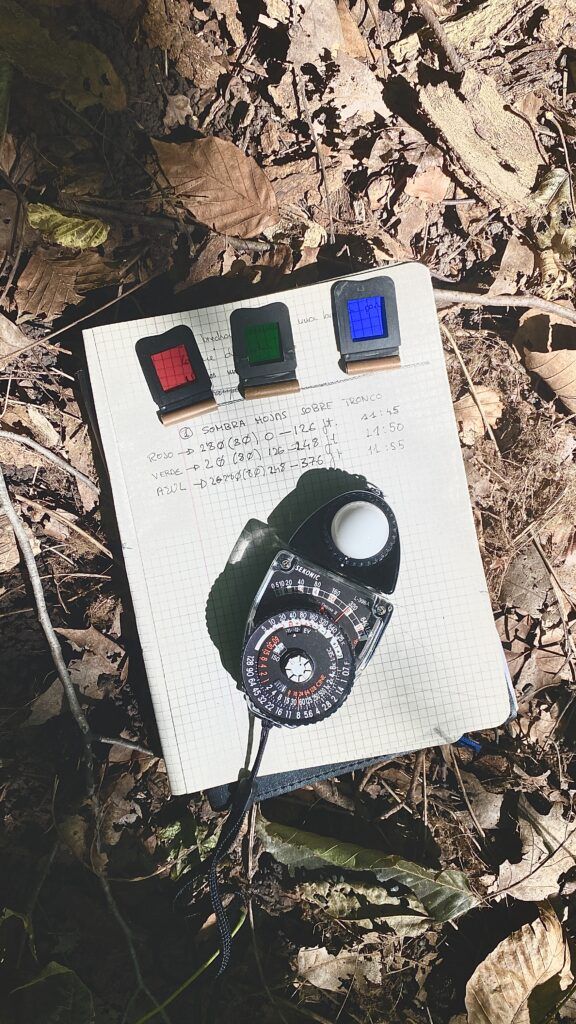

As you say, the whole process required a lot of method and concentration, step by step. That started with the filming, where I kept an exact record of the range of frames in each shot so I could “travel” from one point to another on the reel during copying without getting lost.

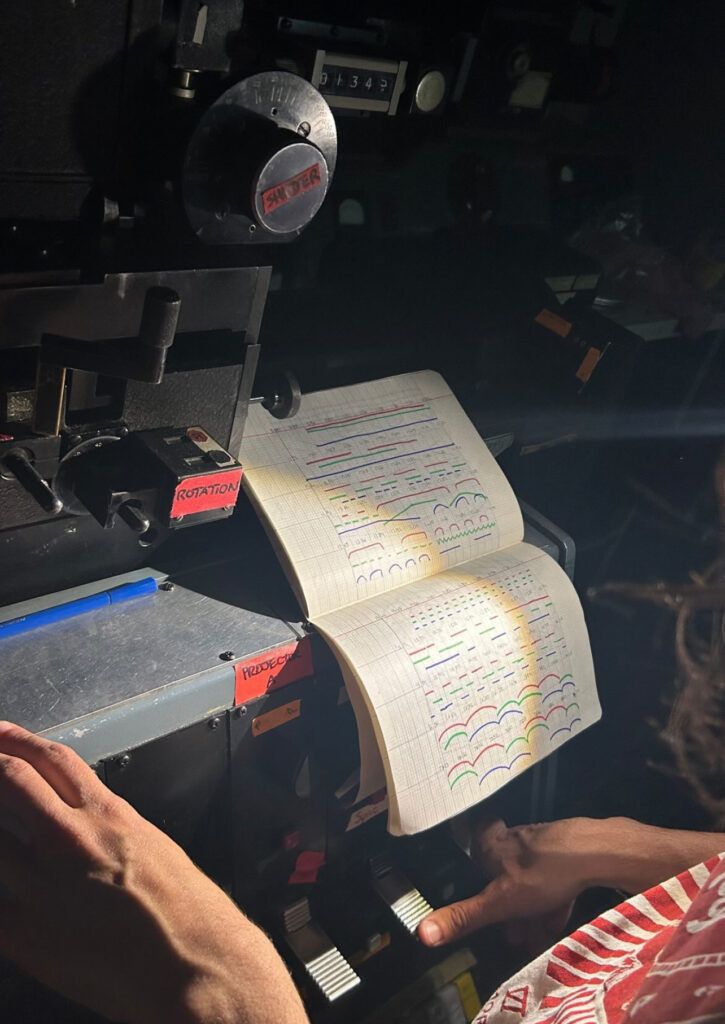

The most complex part, but also the most fun, was writing what I call “musical copy scores”. To do this, I created a template with 72 frames per line, counted in groups of 8, on which I could compose the piece and combine the RGB layers in multiple ways before working with the printer, turning the Oxberry 1700 into a rudimentary “musical instrument”. After a time, I became able to play those scores in real time.

This composition—albeit influenced by the structure of the score itself, which on its own provides a certain sense of order—didn’t follow any metric rule, but rather I committed myself to playing and testing possible ways of writing and combinations of layers.

But before reaching that point, I needed to establish a connection with the motifs and locations being filmed. This is because, aside from technical issues, the project is also based on more subtle issues such as observation, silence and proximity. Within the methodological process, I’d also like to mention the time spent observing and walking among trees (or buildings), observing the passage of light, its arc over the day, waiting for the wind or seeking clouds.

The gesture of filming was not a trivial matter at any time. It’s just as important to know how to measure light as it is to know how to place yourself on the side of instinct, relying on your body for the synthesis that triggers the decision of where and when to position yourself to open your eyes and look. And I think this filters through and resonates in the final outcome, and is what allows the piece to also act as an invitation to take a chromatic walk, beyond the technical ingenuities—suspending both judgement and language—and becoming for a moment a little animal looking at the world in amazement. Becoming a turtle, for example.

—How has it been received among Toronto’s experimental film community?

I must confess that I became so absorbed in creating it that I had little time for socializing. I always need more time for these things. But it was great to be able to share the process towards the end of the residency with a screening open to the public, which was attended by very interested and interesting people who I was able to chat with afterwards. I felt it was very well received, though all of the material was shown in a somewhat disorderly way, and it was the first time I myself watched everything I had done.

—And what feelings did it give you to work in a space like LIFT?

It was great! Working at LIFT is definitely an experience I have a lot to be grateful for: first of all, for the entire team, for the technical department to whom I literally owe this work’s existence, and for the administration department who do an incredible job keeping this space alive and facilitating the creative work of many artists. I would have loved to stay there a lot longer, to be honest.

—Your work stands out in technical exploration and knowledge of creative processes in the photochemical medium. How has your time at LIFT influenced your work’s artistic development? What were you able to explore there?

This project was designed in a very specific way to be able to carry it out in LIFT and in a city like Toronto, where getting lost among trees is quite easy, but also among buildings whose architecture is in no way organic.

Being able to work with the optical printer was certainly a huge leap in terms of my own resources, and without the printer I would not have developed the scores the way I did. What’s more, having 5 weeks with resources in terms of materials and space to concentrate entirely on it enabled me to delve deeper and deeper into the work of printing itself. Every 90 seconds of footage has about three or four hours of printing behind it, so just imagine the hours I spent with my friend Oxberry. That required a lot of patience and method, which is a big contrast to my previous, much more chaotic creative processes.

In some ways, I feel like my time at LIFT has given me more solid ground to stand on.

—What stimuli do you find in the analogue format of motion pictures, and why do you think this choice helps your creative process?

There’s one thing I love, and that’s the sense of immediacy in the relationship with light and its physicality; as soon as it touches the film, an indelible wound is created in it. It’s as if filming were an act of consciousness in which the clicking of the camera is synchronized with one’s own heartbeat.

This also appears in the gesture of one’s entire body, which leans towards the light. I had never felt the sensation of drawing in space when recording digitally, nor of having light and its trajectories pass through me. I suppose that’s where my interest in dance and somatic practices intertwine.

I also get the feeling that the analogue format is resistant to being easily learned, and it forces one to develop instinct and attention. It’s a paradox that we work with light in such darkness, and that the way to free the gesture of film involves turning the camera into a body and one’s eyes into light meters. Of course, I still have a long way to go to get there, but that path appeals to me.

And then there’s something about not being able to tame it entirely, at least in the “amateur” way that I approach it, where the idea of having absolute control over the images is simply absurd. And I like that. I think we should stop treating images as a means to say what we want to say, and learn to step aside and let them do what they will.

Oh! And the impossibility of achieving an immediate result. The idea of waiting as a form of temporality is not only being threatened, but is also very poorly understood. Yet it’s full of treasures!

—What stage of the process is the project currently at, and what are the next steps going to be?

I’m currently arranging the material with the idea of making a projection with three projectors, and working with an analogue synthesizer that’s driving me crazy, so as to adapt the copy scores to MIDI format. I don’t know if that will end up in it, but I’m going for that. And now I have my mind set on (S8)!

The Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) is Canada’s foremost artist-run production and education organization dedicated to celebrating excellence in the moving image. LIFT exists to provide support and encouragement for independent filmmakers and artists through affordable access to production, post-production and exhibition equipment; professional and creative development; workshops and courses; commissioning and exhibitions; artist-residencies; and a variety of other services. LIFT is supported by its membership, Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council, Ontario Trillium Foundation, Ontario Arts Foundation, the Government of Ontario and the Toronto Arts Council.