JUAN SEBASTIÁN BOLLAÍN

LET’S BE REALISTIC, DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE

Wednesday June 2 | 4:30 pm | SALA (S8) PALEXCO | Get your free ticket here

We have decided to use one of the most famous mottos of May 68 (traditionally attributed to Herbert Marcuse, though it is actually a synthesis of several of the ideas he put forward, turned into a slogan) as a title for this section. But do not get us wrong: our point is not to connect Bollaín’s film legacy with the student protests and the workers’ struggle, but to bring to the front the outstanding wit and lucidity that underlie the wild utopias represented in his films. It takes a brave, revolutionary spirit to project the impossible in a world where reality has narrowed to the point it becomes asphyxiating. Just like when one first discovers Fourier or Morris (his titles How We Live and How We Might Live and Useful Work versus Useless Toil are particularly revealing in this light), Bollaín’s work makes you feel relieved –the relief of having found a reassuring clarity, the joy of being able to ascertain that someone who has been properly trained to do so (Bollaín is not only a filmmaker, but an urbanist and an architect) has made an effort to project cities that revolve around pleasure and the provocative art that stems from asking ourselves how we might live –the kind of art that lets our imagination run free.

We have decided to use one of the most famous mottos of May 68 (traditionally attributed to Herbert Marcuse, though it is actually a synthesis of several of the ideas he put forward, turned into a slogan) as a title for this section. But do not get us wrong: our point is not to connect Bollaín’s film legacy with the student protests and the workers’ struggle, but to bring to the front the outstanding wit and lucidity that underlie the wild utopias represented in his films. It takes a brave, revolutionary spirit to project the impossible in a world where reality has narrowed to the point it becomes asphyxiating. Just like when one first discovers Fourier or Morris (his titles How We Live and How We Might Live and Useful Work versus Useless Toil are particularly revealing in this light), Bollaín’s work makes you feel relieved –the relief of having found a reassuring clarity, the joy of being able to ascertain that someone who has been properly trained to do so (Bollaín is not only a filmmaker, but an urbanist and an architect) has made an effort to project cities that revolve around pleasure and the provocative art that stems from asking ourselves how we might live –the kind of art that lets our imagination run free.

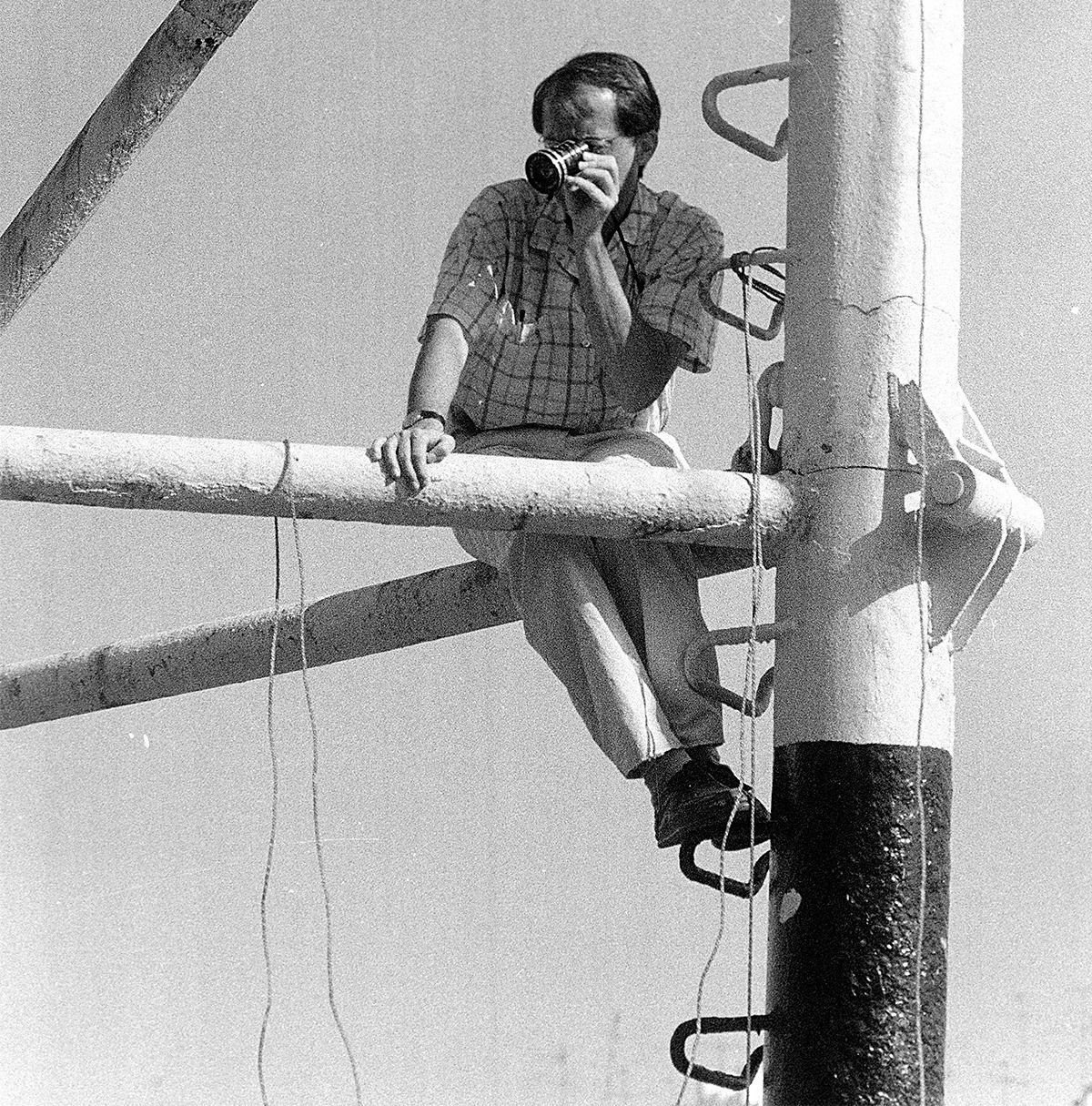

Born in Madrid in 1945 and transplanted to Seville when he was 9 years old, Bollaín took his first steps as a self-taught filmmaker at the age of 14, when he was given an 8mm camera. As he himself recalls, he started “inventing cinema” in the very act of filming, which led him to create his own visual language and procedures. Since then, cinema has been a big part of his life, from his psychoanalytical fiction films and the documentaries he made in his youth to the fiction features he made for television. At the same time, he developed a career as an architect and urbanist. Bollaín is a prolific author, whose work we wish to honor here with a selection of his films. We have curated a program featuring a series of films that he made in the 70s, and which represent a milestone in the history of Spanish cinema. In them, Bollaín’s eagerness to experiment comes together with his unique sense of humor and his unparalleled creative vision.

The first program we’re devoting to Bollaín’s work includes two commissions that were made to him by the associations of architects of Cádiz and Seville. The first one, La Alameda ’78 is a film that was intended to record the configuration and idiosyncrasy of the eponymous Sevillian neighborhood, which was back then threatened by an aggressive urbanistic plan that –if it would have been successful– would have ended up with the eviction of its inhabitants, leaving the area unrecognizable for good. With a creative editing that departs from the usual sound/image relationship in film, Bollaín presents the accounts of the neighbors, who speak about community and marginality in the area –a place that had been known for hosting flamenco parties in the past, and which had become a red-light district and a home to the lower classes. But La Alameda ’78 goes beyond mere documentation: the film lets us see the process of its very making and successfully integrates allegorical resources in the way it depicts a model of the neighborhood –a model that, at the beginning of the film, is sold to the highest bidder in a flea market (as was expected to happen with the real neighborhood) and is then subjected to adverse conditions that generate striking images. The second film of this program, C.A. 79. Un enigma del futuro is also the result of a commission, this time related with an urbanistic expansion in the city of Cádiz (which isn’t an easy task –the city is located on an isthmus) that did not happen in the end. The tools that Bollaín chooses for this film are quite different from the strategies put into practice in La Alameda. Instead of focusing on the past or the present, he puts together a science fiction film where the discussed matter is approached from the perspective of a fictional future (the year 4000), when a group of archeologists discover what for them are a bunch of enigmatic remains of a mysterious ancient city. This allows Bollaín to delve into contemporary matters in a creative, open-minded way.

The second session is an invitation to approach Bollaín’s famous tetralogy Soñar con Sevilla (Sevilla tuvo que ser, Sevilla en tres niveles, Sevilla rota, and La ciudad es el recuerdo): four films shot in super 8 that are the result of a research project that funded with a scholarship granted to the author by the Spanish foundation Fundación Juan March. This research project also led to a published work, El cine y el hecho urbano. Soñar con Sevilla offers a compilation of inventive images that portray a utopian Seville through performative actions, creative collages, and special effects. Seville is a city where tradition plays a major role, and whose urban landscape goes back many centuries. In this light, Bollaín’s visions are doubly iconoclastic: his films called for hedonism and citizen participation, and ridiculed the dictations of capitalism and conservative doctrines. This program is completed by two pieces that account for Bollaín’s experimental, inventive spirit: a selection of excerpts from Seguimiento del rostro de Felipe, a unique record of his first son throughout his childhood and teenage years, and several pieces from his activity at the Sección de Cine Experimental de Arquitectura (association for experimental cinema on architecture) that he co-founded with Jaime López de Asiain –and also directed between 1967 and 1971– at Seville’s school of architecture. The purpose of this initiative was to make the most of the expressive tools of cinema in order to cast –and capture– a critical glance on architecture through both the study of historical buildings and modern housing units.

PROGRAM 2

SEGUIMIENTO DEL ROSTRO DE FELIPE | Juan Sebastián Bollaín, Spain, 1975-1993, super 8, 10 min.

A selection from this series of super 8 films in which Bollaín records his first son’s childhood and teenage years. As Bollaín himself puts it, “Every month I filmed Felipe’s bust, from his birth till he was 18 years old (when my son, still a teenager, refused to continue posing for the camera). I arranged and edited scenes of 30 frames per month, using quick successions of 12 scenes per year. This allows us to see the child grow in a smooth, continuous way before our eyes. 30 frames per month equals, in a way, a frame per day, which means that a whole life seemed to parade live before the astonished viewer.”

SECCIÓN DE CINE EXPERIMENTAL DE ARQUITECTURA

Co-founded by Bollaín and Jaime López de Asiain in 1967 at Seville’s school of architecture, Sección de Cine Experimental de Arquitectura was a research group devoted to exploring the potential of cinema as a medium of expression and a tool for disseminating urbanistic challenges and other city-related issues. “Our goal is to free ourselves from the asphyxiating linear systems of information, to open to the inherent potential of images, considered both individually and in relation with other images. We wish to delve into the different perspectives from which we might be able to access the totality of a given reality. Architecture is out there to be experienced and judged; it must not be passively accepted. This way, if we happen to find in it something we don’t like, we’ll be able to change it.” (Excerpt from the Sección’s manifesto)

SEVILLA TUVO QUE SER | Juan Sebastián Bollaín, Spain, 1979, super 8 a 16mm, 9 min.

Sevilla tuvo que ser is the first film of Bollaín’s tetralogy Soñar con Sevilla. A fictional report by an American TV channel praising the virtues of the very advanced city of Seville, with all its urbanistic improvements: from the public broadcasting of Pornography Week to the curious methods used for informing the citizens about the weather and encouraging them to participate in the arrangement of the city.

SEVILLA EN TRES NIVELES | Juan Sebastián Bollaín, Spain, 1979, super 8 to 16mm, 9 min.

A film report from a fictional archive of 1995’s Seville that brings to us the glorious results of the city’s urban improvements that have turned it into a three-level city: 1) the rooftops, now home to criminals and outsiders, which have contributed to reduce violence and criminal activities thus resulting in the elimination of prisons, 2) the street level, which now hosts the working population, commercial establishments (a “paradise” of unbridled productivism), and 3) the subsoil, where the Seville of yore is still alive.

SEVILLA ROTA | Juan Sebastián Bollaín, Spain, 1979, super 8 to 16mm, 10 min.

A film halfway between surrealism and the nouvelle vague, which breaks with linearity thanks to a shocking editing. The result? A satirical, oneiric fiction that imagines a new kind of city. The piece includes an explicit manifesto signed by the author that invites the viewer to look at Bollaín’s tetralogy from a new perspective.

LA CIUDAD ES EL RECUERDO | Juan Sebastián Bollaín, España, 1979, super 8 to 16mm, 14 min.

A sort of “symphony of a city”, the most quiet and poetic of the films that conform the tetralogy, La ciudad es el recuerdo is an account of the collective memory of Seville’s inhabitants. The first part of the film shows us the passage of time: we see days and seasons go by through a series of time-lapses. In the second part, to a soundtrack of sevillanas, several incisive collages delve into the dangers of commodification.