This year one of the episodes of Camera Obscura is devoted to Jodie Mack, who visited the festival back in 2014 with her program Let Your Light Shine. On the occasion of this new encounter with her work, we bring back a conversation we had with her regarding her interest in prints and patterns.

What was the moment when you started to develop an interest in prints and patterns? What led you to choose motifs like patchwork blankets (Blanket Statement #1, 2012; Blanket Statement #2, 2013), wallpaper (New Fancy Foils), paramecia (Persian Pickles, 2012), and lace (Point de Gaze, 2012)?

That’s a good question! I grew up in London, where I think there is great sensibility when it comes to graphic design, but I don’t think that resonated with me until I started creating these pieces with patterns…

It’s something that can be seen as abstract art, but it’s not, it’s more popular and present in our everyday life.

Yes. What I try to do is call attention to how the motifs in abstract art play a role in our daily lives, I like to delve into how people believe they don’t like abstract art, when the things they wear or buy for their homes are actually the same things and use the same motifs as many abstract paintings. My first pattern films were an inventory of my own belongings –it’s the case with Posthaste Perennial Pattern and Rad Plaid, both from 2010. In them, I try to create conceptual abstract animation, bringing into play the role of abstract animation in itself, which is tricky, because you can’t make an abstract film about something –it stops being abstract. I wonder if it’s possible to make an abstract film about abstraction, and how a standard audience would digest that.

Your work is filled with abstraction. However, that abstraction is full of meaning.

Exactly. When patterns move quickly, there is an illusion of simultaneity, which in some ways encompasses many things you remember because you’ve seen them in your own house, in shops, or in the streets. I used to just take what I had, but now I try to be more pragmatic in these decisions. I started out making films without a camera, so I very early developed an interest in symbols. When you make films without a camera, your canvas is so small that symbols emerge very quickly. There are so many possible images: a circle, a peace symbol, a face that becomes a stop sign, a flower, or whatever. I’m interested in how all these patterns might work at a more complex level.

Paramecia, for instance. With them, I opened the door to post-psychedelia. In fact, paramecia started out as religious motifs in many cultures and countries, and later on, as the psychedelic movement appropriated them, ended up meaning something totally different. So, what at the beginning was a representation of God would later become a symbol for the anti-war culture. Nothing of this is said in the film (Persian Pickles), but I try to organize the patterns chronologically so that one can have an idea of how the motif evolved over time.

In my lace film (Point de Gaze), on the other hand, I tried to explore a certain kind of delicate voyeurism or the intimacy of cinema resting on your own body.

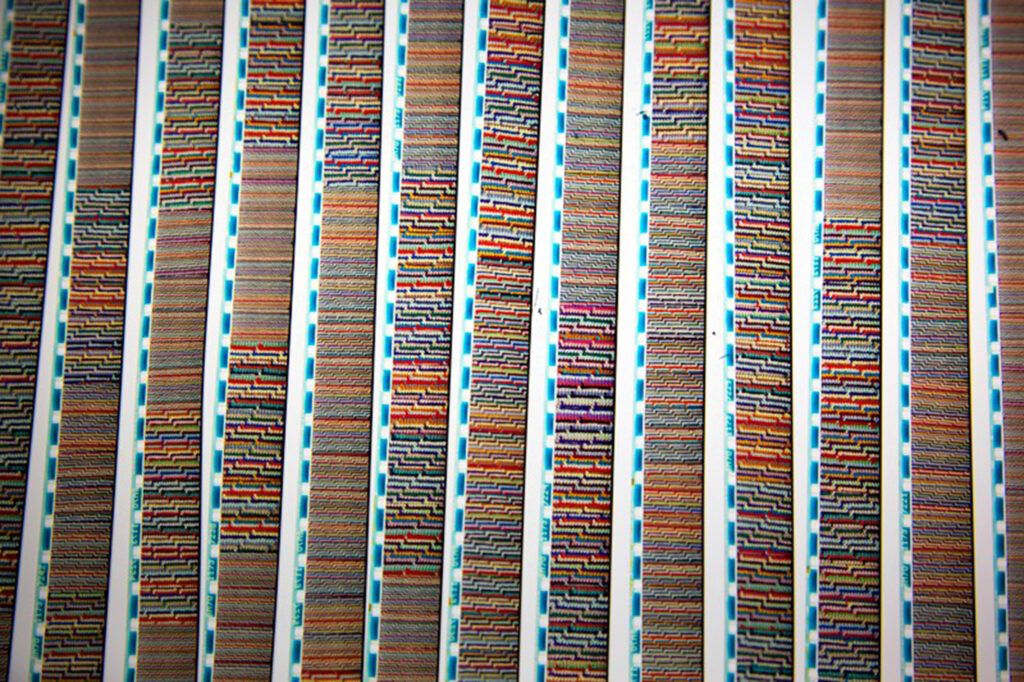

I also started working with quilts made by women, and in that film (Blanket Statement #1), the use of images printed over the sound area of the film strip creates a tension between the safety of the domestic sphere and the aggressivity of the sound sphere, because the sound of the optical strip is very abrasive, while the quilts are soft and warm. So, it is about a certain domestic distress.

And about the passive-aggressiveness of domesticity.

Yes, about the passive-aggressive. For instance, I’m currently working on a series of films that can be labeled as stroboscopic ethnography, or stroboscopic travel journals. I started with Mexican motifs, then traveled to different locations in the United States to see how these same motifs have entered another country. Something that unexpectedly emerged from this is that these films explore work in many ways, because it’s inevitable to wonder where all these things come from, what industries produce them and how they are made. In Mexico I realized I would bump into many handmade objects that have now become something else. Güipil’s embroidery, for example, used to be handmade and now they’re made with a machine. As I’ve been collecting materials over these years, I think that I’ve developed an interest in the evolution of work and production methods, which is something that is also present in Let Your Light Shine. These changing businesses: fashion and the production of cheap goods that one can buy for their home and which can be used for providing the domestic sphere with spectacular moments.