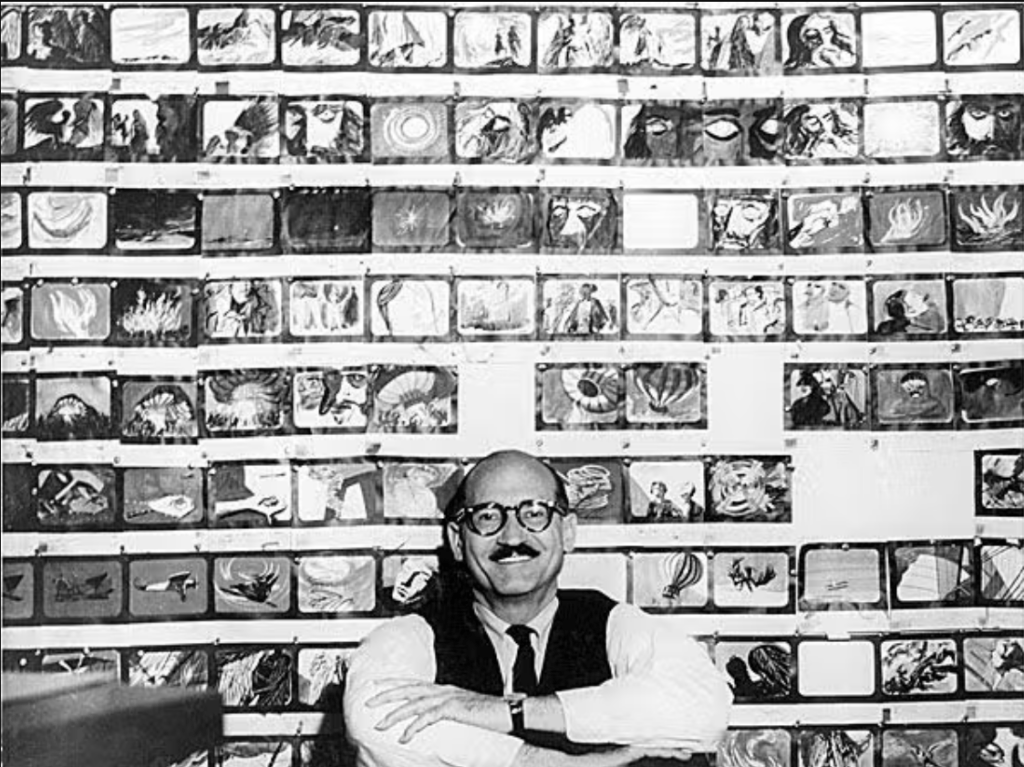

As regards the carte blanche for Light Cone, structured by Miguel Armas based on colour, here we have a textby the filmmaker and expert in visual music William Moritz about Jules Engel, one of the filmmakers present in the selection.

Jules Engel’s films, uniquely among the leading exponents of abstract animation, exhibit a thoroughly Post-Modern sensibility: witty, eclectic, versatile, literate but accessible, classical but popular.

Jules had already begun creating abstract graphics in High School, and at the same time discovered George Balanchine’s choreography for the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, which led him to an ardent interest in the art of dance. This in turn led him to the world of animation, since Disney Studios hired him to supervise the design of choreography for the dance numbers in Fantasia. Engel was by then devoted to his abstract oil painting, but he still applied all his talent (and his knowledge of all aspects of Modern Art) to devising witty, dynamic sequences: the brightly-colored stylized “Russian” flowers seen from a low angle against a black background, or the striking perspective shots in the “Dance of the Hours” which show distant alignments of ostriches between the close-up ankles of the prima ballerina, combine the choreographer’s dynamic sense of timing, gesture and pattern with the contemporary artist’s harmonic sense of color and form in tension and balance.

These parallel tributaries, dance and painting, flow throughout Engel’s own animation films, creating a subtle interchange of layering currents and eddies. In films like Shapes and Gestures and Wet Paint, one is first struck by the graphic suppleness and ingenuity –and it is hard not to think: “This is what Kandinsky might have done if he had made films.” But, of course, Kandinsky did not make films, and his paintings do not really imply the intricate developments of changing trajectories, elapsing relationships, temporal relapses or fluid chronology that Engel’s films enact.

Engel’s refined plastic sensibility (continually conscious of a complete range of styles and philosophies in Modern Art) is matched by his refined spatial/temporal sensibility, fed not merely by “high” classical ballet, but equally by the expressive modern dance of Martha Graham, the experimental conceptual dance of Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown, and truly eclectic, the “low” Broadway dance of Agnes DeMillwe and Jerome Robbins (Engel’s Rumble suggests West Side Story), and even sports as a kind of ritual choreography (as in Engel’s Play Pen).

This confluence of art and dance perhaps reaches its most complex relationship in a film like Landscape, in which pure color frames with no imagery melt and flicker into one another. Engel calls it “Color Field painting in Time,” but again, as with Kandinsky, the very addition of Time and sequence to Color Field canvases constitutes a daring extension of chromatic possibilities, while the reduction of choreography to off-on sequences with no internal gesture or articulation rivals the most radical experiments of John Cage and Merce Cunningham in minimal design. Yet Engel’s result in Landscape is an exciting, accessible experience that fascinates and intrigues the viewer –a tribute to Engel’s artistry.

No less complex are referential films like Villa Rospogliosi and Gallery 3, which consciously evoke the ironic antithesis of exhibition in a museum/gallery and exhibition in a movie theater. The outline of Villa Rospigliosi (a fictional Italian museum) remains on screen throughout the film, reminding us (like the mirrors in representational paintings, or like the serial imagery of “Black Windows” in Engel’s own paintings of the 1960s) continually of the viewing space (as a doubly-coded self-reference, or displacement) which can show equally the the ascetic calligraphy of Cy Twombly, the naive “magical” charm of the bird trapped in an illusory Thaumatrope cage (or is it a real pigeon whose liveliness outside the gallery window distracts from the “nature morte” paintings inside?), and dazzling Post-Modern collages (simultaneously referencing painters Rosenquist and Rauschenberg as well as filmmaker Pat O’Neill) in which repetitive cycles of representational figures brush shoulders with non-objective forms. Elizabeth Bartfai’s ravishing and clever collage of moments from Respighi’s “Botticelli Pictures” brilliantly reinforces this meditation about Art and how we see it.

A similar conceptual drollness (worthy of Duchamp or Engel’s friend Man Ray) informs Accident, a film born from one of Engel’s dreams. The running dog, like the motion-analysis cycles of Muybridge, seems to be the very archetype for Animation itself, yet a clever simulation of the dog being erased transpires before our eyes, through careful animation! What does it mean? Engel says, “My aim is to discover problems, not to solve them. I want to find things that you didn’t know existed.”

A parallel instance of conceptual reflexiveness in Engel’s wholly non-objective films would be the illusion and reality of Wet Paint, in which the insinuation of accidentally-spilled ink that would be running across the paper in random, aleatory oozes displaces the graceful liquidity of the careful animated choreography. The title, by the way, is a “readymade,” an object Engel found on a park bench.

A comparison of two of Engel’s computer graphics also highlights the diversity of his approaches. In Silence, Engel mixes delicate black-and-white patterns which subtly flicker to produce brief sparkly afterimages (rather like the patterns generated when you close your eyes and press against the lids) with the written word “silence”, suggesting an analogy between Cage’s advanced music and a possible kind of optical silence. By contrast, Times Square captures a noisy analogy between city architecture with its garish construction clanks (referencing the famous New York site) and the serene promise of Modernist “Constructivist” art and architecture (referencing the “pure” mathematical operation of squaring multiplications – or is it the arena of modern Physics in which Time is a player?)

Many other aspects of Engel’s films deserve praise. I have noted how much “wit” (in the finest sense) his films display, and, remembering the old adage “Brevity is the soul of Wit”, one must further laud Engel’s sense of timing by observing that most of his films are very brief indeed, charmingly so, for they leave the viewer longing to see them again.

In stressing the poise of art and dance in Engel’s films, I have neglected the musical accompaniments. Engel makes all of his films without reference to sound, as pure optical compositions. When the visual images are completed on film, he commissions a musician to compose a sound score which will be a suitable counterpoint to the picture. Occasionally, the music and visuals seem to synchronize very closely, but most often they work in parallel, alternately agreeing and disagreeing, each with its own integrity. This effect suggests an analogy with Calder’s Mobiles, which also combine discrete elements in flowing patterns of quasi-aleatory choreography of co-incidence. In any case, this give and take –together with the wide range of musical styles (from jazz to sound collage to electronic synthesis)– offers a stimulating and provocative level to the viewer’s experience.

Engel has also done quite a bit of representational filmmaking, from documentaries about his fellow artists to the imaginative animations of Gerald McBoing-Boing, Madeline and Icarus Montgolfier Wright. If ever an abstract artist needed to prove that he could perform adequately with realistic material (which, of course, he should never have to do), Engel could point with justified pride to Coaraze, one of the most perfect and whole films in our literature. In a small village perched among remote French mountains, Engel’s cameras lay bare the most essential mysteries of human experience. From the dizzy pitch of cobbled walkways and the regimented tiles of sagging roofs, he exposes the miracle of light and shade, positive and negative, with an astonishing freshness that reminds us of the luminous intensity of Vermeer or Weston. Simultaneously, his patterns of camera movement and stationary viewpoint (are these still photos? still lives?) form a “silent” choreography that questions the nature of movement, of accomplishment. And in the middle of this contemplative landscape, he also finds essential, existential ironies: this medieval environment co-exists today to be exploited by high-tech cameras, and if we would deny that we are related to these “primitive”, quaint people and places, he ruthlessly follows the savage play of school children in the street, kicking and jeering each other in an uncomfortably familiar fashion –the violence of their “choreography” re-defining the serenity of passive architecture, of innocence and maturity. To have made just this one film would have been enough for most men; for Jules Engel, distinguished and consummate Post-Modernist, it was merely one milestone among dozens of varied, inventive artistic achievements he would accomplish subsequently.