- In addition to the performance Contra Jour, which closes this year’s festival, we will get the chance to see a handful of films by Leah Singer and Lee Ranaldo from recent decades, preceded by a conversation with the artists.

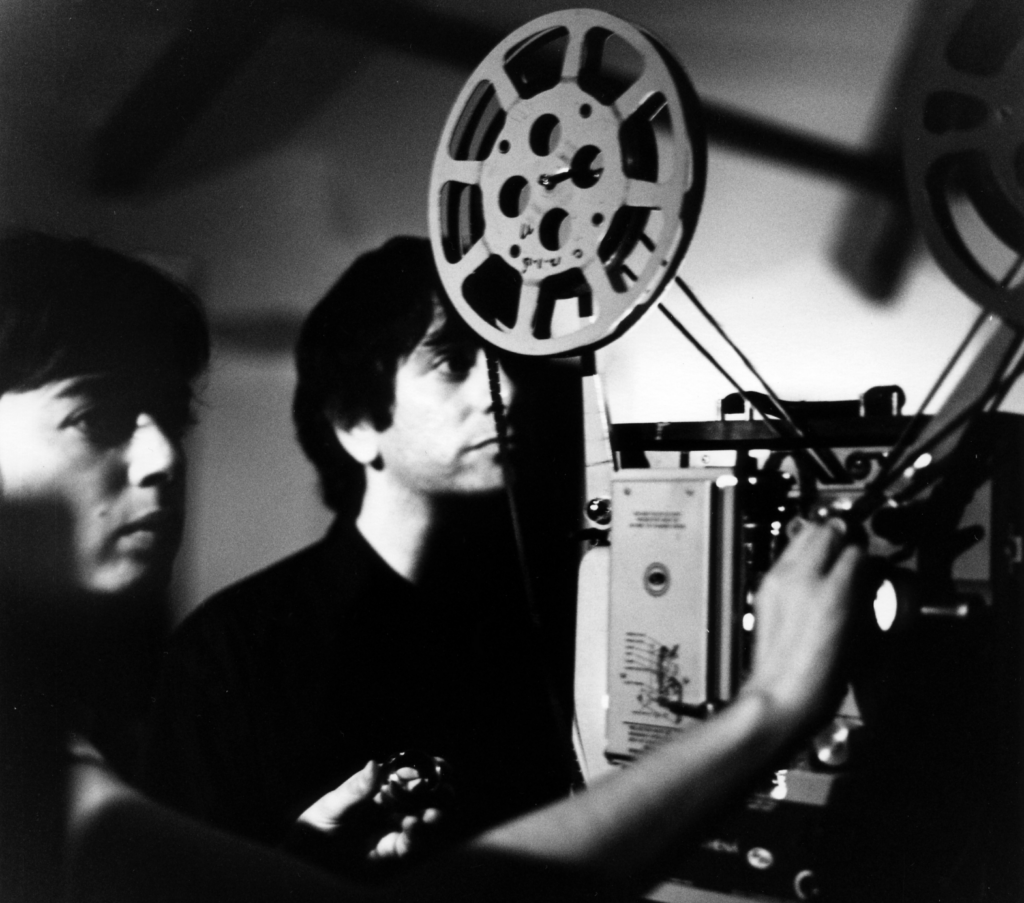

Singer and Ranaldo’s association began in the early 1990s, when the two began to combine knowledge and interests. Lee Ranaldo hails from Long Island. He studied at Binghamton University, whose film department was founded by Larry Gottheim and where Ken Jacobs, Hollis Frampton, Peter Kubelka, Ernie Gehr and others have taught. Ranaldo also took his first musical steps with the New York avant-garde, playing with musicians like Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca. It was the New York where the punk of the Ramones met no wave in a panorama where underground cinema was directly connected with the music scene. This was the case of the films by Vivienne Dick, Scott B and Beth B, and Amos Poe (with his seminal 1976 film Blank Generation with Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Television, Talking Heads, the New York Dolls and more). Ranaldo began his career in Sonic Youth in that breeding ground at the beginning of the 80s, in powerful years of experimentation for the band. Leah Singer, a writer and multimedia artist originally from Winnipeg, Canada, moved to New York in 1988. She too was educated in film, photography and painting, and also ended up getting involved in New York’s improvisational music scene in those years.

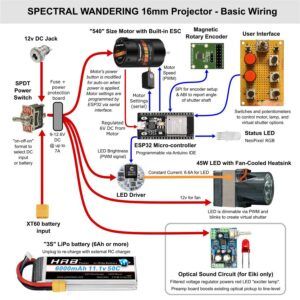

With this background, the two began to collaborate in 1991, and in fact some of the films that make up the selection we will be able to see imply some kind of interdisciplinary collaboration between the two, even when the authorship belongs to one or the other. In works like Here (1992), showing desolate urban landscapes with a somewhat melancholy air, the soundtrack is an improvisation by Ranaldo. The work, in black and white, combines moving images with other halted ones, details of a car journey along endless highways, car parks and motels, with closed shots of details of the landscape of faces. In Here, Singer uses a discovery she would also explore in her performances with Ranaldo, which is the use of a still photography camera loaded with Super 8 and 16mm film. Singer thus prints on the entire surface of the film, in fragments that she then manipulates live with analytical projectors, machines designed in their day to study cinema and with which it is possible to stop and slow down the image, which a normal projector could not do without the film burning. This has been fundamental in Singer’s work with images, which has had a significant element of live intervention over the years. These performances produce versions in the form of a single-channel film, which we will see in this session. In one of the cases, it is the recording of a performance by Sonic Youth and Pavement that is then subjected live to the intervention which, by slowing down and stopping the film, gives a ghostly air to the images, also taken obliquely in contrast to the spectacular nature and splendour of mainstream rock and roll. There is quality accentuated by the asynchrony of the sound, recorded in another live performance by the band. The concert is seen from within, with introspection, which is related to the aesthetics of filmmakers like Jem Cohen, also strongly linked to the independent music scene.

Leah Singer has also collaborated with other bands from the noise rock scene, such as Band of Susans. That collaboration produced The Last Temptation of Susan (1994), made with Singer’s still photo camera technique. It is a piece arranged to the rhythm of a song by the band, a New York night symphony, its crowds and its neon lights with a couple of brushstrokes of found footage; a visual expression of a certain way of being in the world.

It creates the diary-like recording of something whose presence hovers in some way in many of the films in the session. This is something that is clearly seen in Ranaldo’s piece LS in Central Park (1993): following in the footsteps of Mekas, Ranaldo films happy moments and epiphanies in Central Park. This love portrait of Singer concentrates that enchantment, heightened by the luminous reflections overlaid on the image of her face; bright moving points of light. In a way, Here and Navel Milk Prison (2009) are road movies or travel diaries. In the latter, we accompany a woman and a child on a road trip from the back seat. The soundtrack is a poem written by Ranaldo from emails in his spam folder. It is a collection of random words that interact with what we see, adding another dimension to typical American landscapes seen from a convertible on a sunny day. Isolation (2021) is more of a collective pandemic diary brought together by Ranaldo to the rhythm of his version of John Lennon’s song of the same name.

Drift is one of the versions of the work that has resulted in the performance that we will be seeing under the title of Contra Jour. In Drift we see two screens of images manipulated by Singer: it begins with a striking vision in black and white; on one side a telephone, on the other a hand that we later also see in X-rays. Later on, there are urban views, textures of the plot of a newspaper, thronging crowds. They are still images, slowed down. In the second part of the piece, we see that double projection multiplied by four by projecting positive and negative colour images taken with an 8mm camera: the result of the uncut camera film is a quadruple image on each side. In the background, there is Ranaldo’s sound performance. The dense musical landscape introduces us progressively into what we are seeing. Poetry also intervenes in the form of the spoken word, a river of words that speak of the apocalyptic landscape after the 9/11 attacks and the fall of a New York landmark, the twin towers. It acts as a visceral response to the surrounding horror, working as a kind of antidote to the ruthless media overload.

These are just a few examples of a romantic, creative life together spanning thirty years, a prelude to the cathartic ending that Contra Jour will provide for (S8) this year.